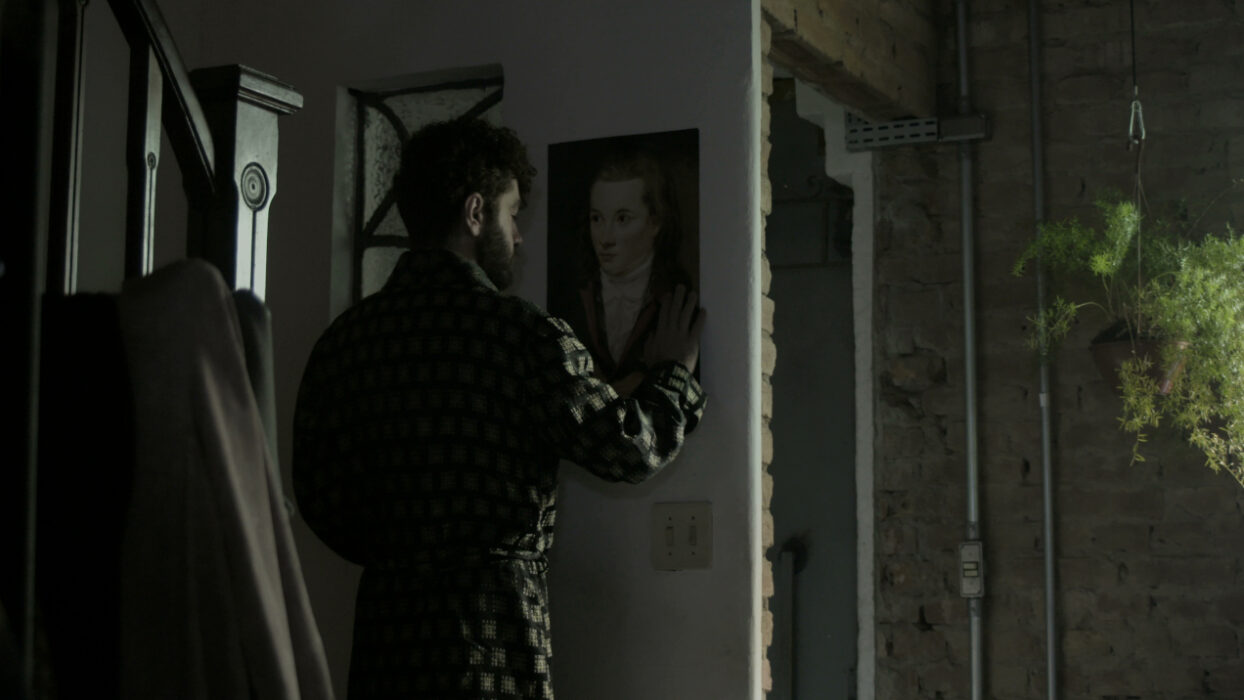

A Rosa Azul de Novalis

Marcello occupies the image from beginning to end and talks about a jumble of things: his passion for coffee, his HIV status, his chronic headaches, his homophobic father, his fantasies of having his father watch his lovemaking with passing boyfriends, his lovers’ passion, his Catholic grandmother or his incestuous brother. At times, he takes himself for Genghis Kahn, Novalis or a French courtesan; at others, he talks about Bataille or the Saint whose name he has forgotten and who, on the scaffold, is said to have taunted his executioner with a startling sense of humour. In all of the monologues that Marcello delivers to the camera, it is perhaps the story of the Saint responding to pain with humour and lively wit that embodies the most sincere part of the self-portrait. With Marcello, Gustavo Vinagre and Rodrigo Carneiro take up the masochistic-sadistic exercise of confession that has now invaded our images, at the point where Shirley Clarke with her Portrait of Jason had left off. In other words, by viewing its theatricality straight-on and by laughing – much like the Saint facing his executioner – at the impasse of cinéma-vérité, which imagines it can get to the very bottom of all that is exposed to its gaze. Here, provocation, the refined taste for blasphemy, are less a means of deflecting the requirements of a confession than a way of turning it into a baroque spectacle – brutally trivial yet just as sacred, in conjunction with Marcello’s formula which serves as a moral: “I’m useless, like everything that is important.”

Jérôme Momcilovic

Rodrigo Carneiro (Carneiro Verde Filmes)

Bruno Risas

Rubem Valdés

Rodrigo Carneiro

Rodrigo Carneiro (Carneiro Verde Filmes), rodrigocarneirocine@gmail.com