Édition 2024

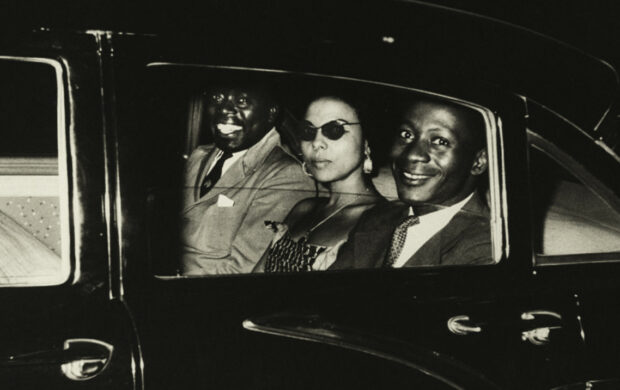

“Taking stock of documentary filmmaking as a cinema of mise-en-scene”: this was the idea that gave shape to this edition of Cinéma du Réel, along with the decision to showcase the work of three filmmakers from different corners of the cinematic map. First, with the first French retrospective dedicated to Claudia von Alemann, a pivotal figure of German feminist cinema and one unafraid to mix different languages and narrative devices. Ultimately, these varied approaches coalesce into a body of work that sits at the crossroads of political, shared and personal experience. Second, with the pioneering figure of independent US cinema, James Benning, an avid explorer of America and a keen observer of its history, whose explorations of the country’s storied and eventful landscape create an experience of time and space. Third, with Jean-Charles Hue, whose films, standing halfway between documentary and fiction, plunge us into the heart of a troubled, dangerous and intense reality, in company of the Yenish community in France and with the social outcasts of Tijuana. Documentary filmmaking spans a vast territory whose porous and changing borders allow for formal as well as narrative experimentation. The competition explores these manifold experimentations through a line-up of French and international productions, short- and feature-length, made by emergent filmmakers and acclaimed directors. Experimentation is also the through-line of First Window, a category dedicated to outstanding debut films put forward by a new generation of filmmakers. Popular Front(s) and Special Screenings complete this line-up of contemporary documentary films which investigate and provide new readings of the world we live in. Cinéma du réel also invites viewers to set out on an alternate, more anarchic, and less definite path. Like parts of a rhizomatic process, films complete each other, look at each another: Marie-Pierre Duhamel spoke of films as “holding hands”. Films reframe the tensions that run through our present, bringing out its rugged complexity, its friction, as well as what is in plain sight: the obvious persistence of colonial power experienced by the inhabitants of overseas territories, as shown by the films of Martine Delumeau and Malaury Eloi Paisley in Guadeloupe, by the films of Cécile Laveissière and Jean-Marie Pernelle in Réunion, and by the films of Florence Lazar in Martinique; and the obvious persistence of colonial power which gradually emerges from Mati Diop’s Dahomey, this year’s opening film. Colonialism is again at issue in Soundtrack of a Coup d’Etat, which draws a connection between the American Civil Rights Movement and independence struggles in African countries. It looms large in Raphael Pillosio’s Les Mots qu’elles eurent un jour, which centres on the story of women combatants during the Algerian War, beautifully portrayed by Yann le Masson upon their release from prison. The portrait of these modern and deeply committed women who fought for freedom in 1962 is a reminder that the fight against the patriarchy is neither new nor over. Feminism, if we so choose to call it, will also be at issue in the retrospective dedicated to Claudia von Alemann, and in the films of Claudine Bories, Natacha Thiéry, Sabine Groenewegen, and Kumjana Novakova, among others. Each of these screenings will offer a chance to reflect on the political experience of women filmmakers, on their work, and on their trajectories. And then there is Gaza: not as the event suddenly bursting into our lives and leaving us stunned, as if by some suspension of time, but as something happening to us all and reshaping the way we consider the present, human relations, and our relation to the world. What is happening in Gaza, at this very moment, informs the way we watch films: not only those coming to us from Palestine, but those from Sarajevo and from the Nagorno-Karabakh as well. Catherine Bizern

-

-

Competition

Running from 6 to 216 minutes, from Japan to Argentina and from France to China, the 37 films in the Competition once again showcase the most outstanding contemporary documentary creations, as world, international or French premieres.

-

Aeroflux

Nicolas Boone

-

Americium

Théodora Barat

-

Arancia bruciata

Clémentine Roy

-

Boolean vivarium

Nicolas Bailleul

-

Capture

Jules Cruveiller

-

Direct Action

Guillaume Cailleau

Ben Russell

-

Gama

Kaori Oda

-

The Garden Cadences

Dane Komljen

-

Homing

Tamer Hassan

-

Imperial Princess

Virgil Vernier

-

Journey into Gaza

Piero Usberti

-

Le Fardeau

Elvis Sabin Ngaïbino

-

Leaving Amerika

Marie-Pierre Brêtas

-

Light, Noise, Smoke, and Light, Noise, Smoke

Tomonari Nishikawa

-

Longtemps, ce regard

Pierre Tonachella

-

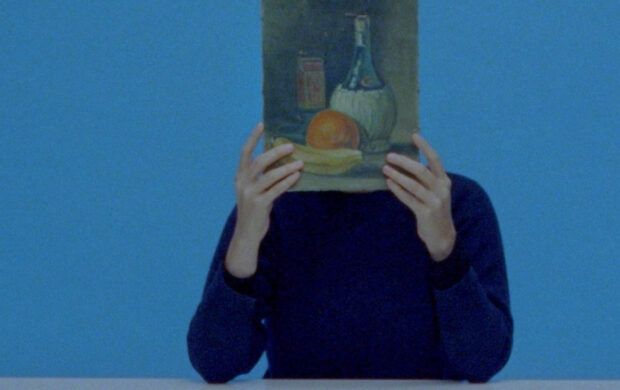

Louis et les langues

Aurélien Froment

-

Marbled Golden Eyes

Kevin Jerome Everson

Lydia Marie Hicks

-

Modèle animal

Maud Faivre

Marceau Boré

-

Les Mots qu'elles eurent un jour

Raphaël Pillosio

-

On the Battlefield

Ray Whitaker

J.P. Sniadecki

Lisa Marie Malloy

Theresa Delsoin

-

Où sont tous mes amants ?

Jean-Claude Rousseau

-

Ozr el wezzah

Mahdy Abo Bahat / Abdo Zin Eldin

-

The Periphery of the Base

Zhou Tao

-

Remanence

Sabine Groenewegen

-

Republic

Jin Jiang

-

Resonance Spiral

Filipa César

Marinho De Pina

-

The Roller, the Life, the Fight

Elettra Bisogno

Hazem Alqaddi

-

Sauve qui peut

Alexe Poukine

-

The Signal Line

Simon Ripoll-Hurier

-

Silence of Reason

Kumjana Novakova

-

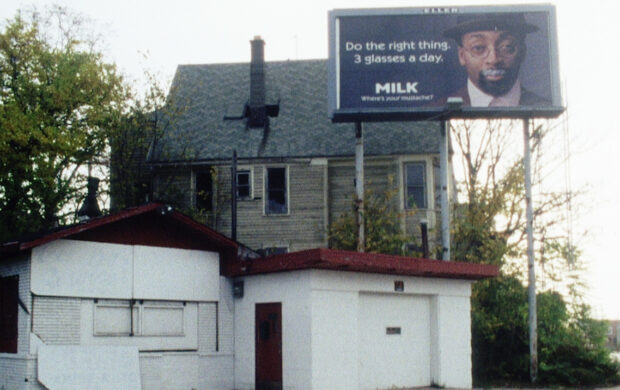

Soundtrack to a coup d'état

Johan Grimonprez

-

Sous les feuilles

Florence Lazar

-

Stone, Hat, Ribbon and Rose

Eva Giolo

-

The Soldier's Lagoon

Pablo Álvarez-Mesa

-

tú me abrasas

Matías Piñeiro

-

Under a Blue Sun

Daniel Mann

-

Vuelta a Riaño

Miriam Martín

-

-

-

First Window

This section highlights young filmmakers and their first documentary works, made as part of their training, from various production workshops, produced by young production companies or outside any structure.

The films are shown in theatres over the course of the festival, giving young filmmakers the opportunity to meet with the audience. They are also available online on Mediapart.fr, where visitors can vote for their favourite film.

-

Comrades

Ulysse Sorabella

-

Des châteaux de sable

Marie Vettese

-

Fatmé

Diala Al Hindaoui

-

I Asked the Factory

Noa Epars

Louis Lamarche

-

In Flux

Taryn Everdeen

-

Loveboard

Felipe Casanova

-

The Mars Project

Louis Rémy

-

Metamorphosis' Chantings or That Time When I Incarnated as Porpoise

Ainá Xisto

-

Skatepark

Fanny Chaloche

Annabelle Martella

-

Taïauts et Chevreuils

Agathe Simon

-

Walks That Won’t Happen

Mina Simendić

-

The Whitest Shadow

Damien Cattinari

-

-

-

Special screenings

Special Screenings feature unreleased films, further expanding our perspective on the multiple facets of contemporary documentary creation. These films resonate with the other line-ups of the festival, and throw light on our reading of the present.

-

44 jours

Martine DELUMEAU

-

Atlantiques

Mati Diop

-

Award ceremony

-

Chroniques fidèles survenues au siècle dernier à l’hôpital psychiatrique Blida-Joinville, au temps où le Docteur Frantz Fanon était chef de la cinquième division entre 1953 et 1956

Abdenour Zahzah

-

Dahomey

Mati Diop

-

Discussion on Exergue – On Documenta 14

-

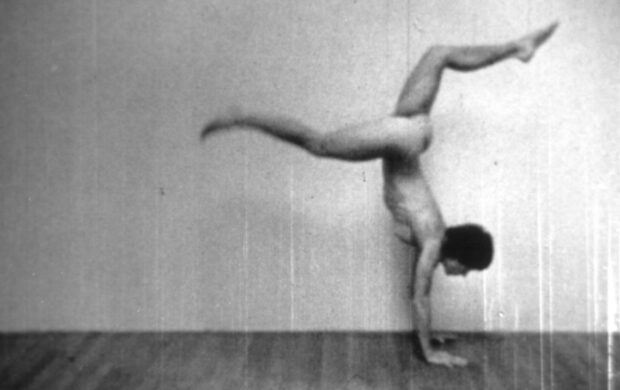

Double Strength

Barbara Hammer

-

Enthusiasm (The Symphony of Donbass)

Dziga Vertov

-

exergue - on documenta 14

Dimitris Athiridis

-

L'expérience Zola

Gianluca Matarrese

-

Femmes d'Aubervilliers

Claudine Bories

-

L'Homme-vertige

Malaury Eloi Paisley

-

Juliette du côté des hommes

Claudine Bories

-

L'Ile au trésor

Guillaume Brac

-

Looking for Robert

Richard Copans

-

Meshes of the Afternoon

Maya Deren

Alexander Hammid

-

Nuit obscure - Au revoir ici, n'importe où

Sylvain George

-

Otherhood

Deborah Stratman

-

Patience, mon coeur

Sophie Bredier

-

Pierre Guyotat, le don de soi

Jacques Kébadian

-

Prove di stato

Leonardo Di Costanzo

-

Rerun of Awarded films

-

Route One / USA

Robert Kramer

-

Séance d'écoute : Cheveux en bataille

Clawdia Prolongeau

Clémence Gross

-

Steelmill/Stahlwerk

Richard Serra

Clara Weyergraf

-

Sur une terrasse à Istanbul - Conversation avec Pierre Guyotat

Jacques Kébadian

-

Vever (for Barbara)

Deborah Stratman

-

-

-

Popular front(s)

Films where the cinematographic gesture in the face of violence is that of a witness but also one that reconfigures the field of memory, a gesture of sharing new principles of intelligibility. Individually and together.

From the Christians’ commitment to political struggles in Latin America to the story of the Farcs’ reorganisation of the guerrilla in Colombia, we revisit the story of how the Latin American oligarchies use violence to hold onto their privileges. This struggle of the poorest for a harmonious coexistence is also found in the small activist community that set up at the roundabout in Le Tampon on Reunion Island. Here in France, walls are the rallying points for the struggle against the patriarchy, the urban space being more than ever claimed as a space of freedom and the affirmation of a collective revolt.

Throughout the programme, situations mired in the violence of war follow on from each other, creating a shot/reverse-shot effect or rather the dreadful propagation of a disaster that repeats itself. This reminds us of the words of Jean-Luc Godard in Our Music “Why Sarajevo? Because Palestine”. Today it is the story of the siege of Sarajevo and the ways in which filmmakers bore witness to this time that inevitably takes us back to Gaza and its population under the bombs, here and now. It is the images of the exodus of men and women forced to leave all their possessions and land in Nagorno-Karabakh, expelled by the Azerbaijani army that suddenly concretises the cruel scenes that we know the Gazans are living through.

The war in Palestine. The films we have chosen, one of which was shot just after October 2023 (No Other Land), documents what the Israeli military occupation means; they also recount the Palestinians’ combat against obliteration. What can cinema do? The question asked by Cahiers du cinéma in their February issue is also ours but is it not a question that each film raises in its own specific way and that it directs not at cinema but suggests that the viewer explore? Popular Front(s) endeavours to create the conditions for this exploration.Catherine Bizern

-

The First 54 Years - An Abbreviated Manual for Military Occupation

Avi Mograbi

-

La Concorde

Sylvestre Meinzer

-

Cosmocide

Nicolas Klotz

Elisabeth Perceval

-

Cries Tear Through The Silence

Natacha Thiéry

-

Far From Michigan

Silva Khnkanosian

-

The Gospel of Revolution

François-Xavier Drouet

-

Guerilla des Farc, l'avenir a une histoire

Pierre Carles

-

No Other Land

Basel Adra

Hamdan Ballal

Yuval Abraham

Rachel Szor

-

Point virgule

Claire Doyon

-

R21 AKA Restoring Solidarity

Mohanad Yaqubi

-

Se souvenir d'une ville

Jean-Gabriel Périot

-

Terla ta nou (Cette terre nous appartient)

Cécile Laveissière

Jean-Marie Pernelle

-

WHAT CAN THE CINEMA DO IN THE 21st CENTURY?

-

-

-

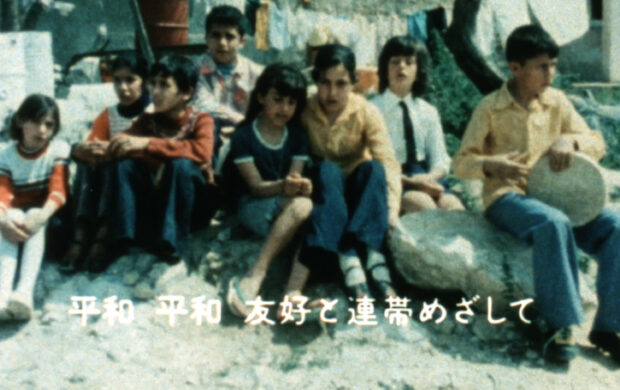

Claudia von Alemann

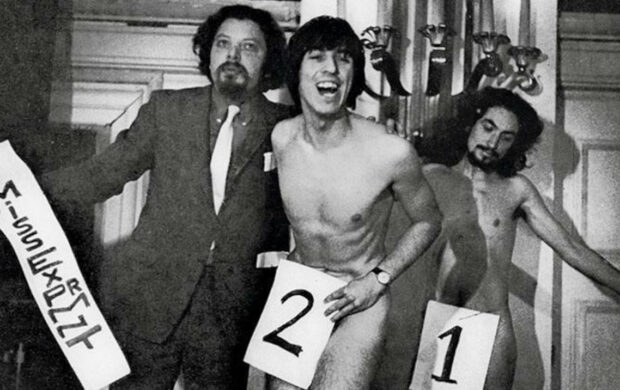

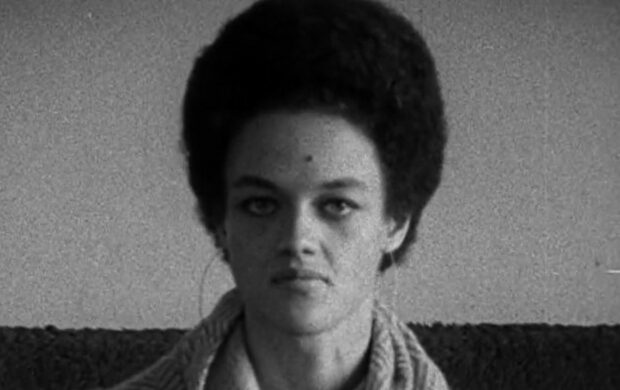

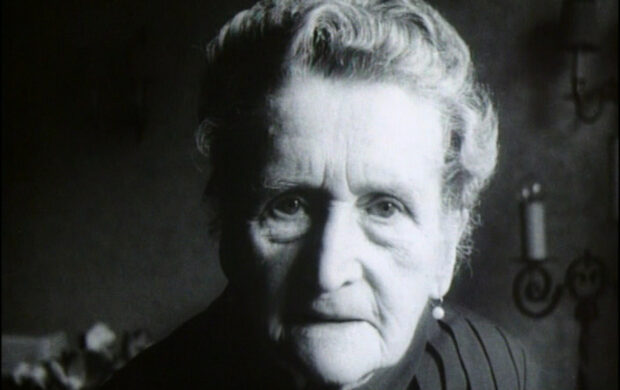

In November of last year, a special programme of films presented at the Berlin Arsenal under the title “feminist elsewheres” celebrated the 50th anniversary of the First International Women’s Film Seminar. The event was first launched by Helke Sanders and Claudia von Alemann, who remains a critical figure of German feminist cinema to this day. The 1960s were coming to their tumultuous end and Claudia von Alemann had just wrapped up her studies at the Ulm Film Institute (where she had got to know Alexander Kluge) when she decided to shoot Knokke-le-Zoute’s rowdy experimental film festival, joined the student movement in Paris, and met up with the founders of the Black Panthers in Algiers. Driven by a desire— shared by others—to make counter-information films, she was also eager to do away with conventional forms. Throughout her career, Claudia von Alemann has taken up and brought together a wide variety of filmic languages: from experimental forms to political documentaries, from films in the first-person to historical fiction.

The history of 19th-century feminism looms large in her work, which includes one book and two films devoted to the topic. However, like Flora Tristan—who believed that the emancipation of the working class relied on the emancipation of women—her films address patriarchy and capitalism in the present tense, tackling both topics head-on in the 1972 film The Point Is to Change It, as well as in Nuits claires and in the films she shot in Thuringia after the fall of the wall.

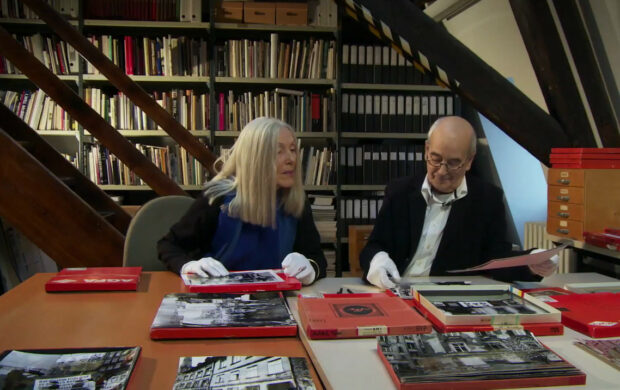

After Nuits claires, the films shot in her home region drew on her family’s story as well as her own, all the while throwing light on the blind spots of German history. From that moment on, her films took a more distinctively biographical turn. They suggest that you cannot speak about others without speaking about yourself, and that you cannot talk about history without delving into your own past.In Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image, the catalogue of “No master territories”¹, a 1976 piece by Claudia von Alemann examines the word “collective”, framing it as a powerful force for thought, resistance, and action. The collective is one of the arguments driving von Alemann’s desire to film and her commitment as a feminist filmmaker. If the intimate is political, then shared experience and the politics of friendship, or sisterhood as we might call it today—as portrayed in The Next Century Will Be Ours and in Nuits claires—are integral to creation. Her latest film, devoted to her friend the photographer Abisag Tüllman, is a graceful expression of this.

Catherine Bizern

_____

¹The exhibition, curated by Hila Peleg and Erika Balsom, was on show at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, in Berlin, and at the Warsaw Museum of Modern Art in 2023.

-

...es kommt drauf an, sie zu verändern

Claudia von Alemann

-

Aus eigener Kraft - Frauen in Vietnam

Claudia von Alemann

-

Blind Spot

Claudia von Alemann

-

Das ist nur der Anfang, der Kampf geht weiter

Claudia von Alemann

-

Denny, Ameise und die Anderen

Claudia von Alemann

-

DISCUSSION WITH CLAUDIA VON ALEMANN

-

Exprmtl 4 knokke

Claudia von Alemann

-

Die Frau mit der Kamera

Claudia von Alemann

-

Kathleen und Eldridge Cleaver in Algier

Claudia von Alemann

-

Lichte Nächte

Claudia von Alemann

-

Das nächste Jahrhundert wird uns gehören

Claudia von Alemann

-

November

Claudia von Alemann

-

The intimate and the political

-

THE POLITICAL EXPERIENCE OF WOMEN FILMMAKERS, SINGULAR PATHS

-

War einst ein wilder Wassermann

Claudia von Alemann

-

Wie nächtliche Schatten - Rückfahrt nach Thuringen

Claudia von Alemann

-

-

-

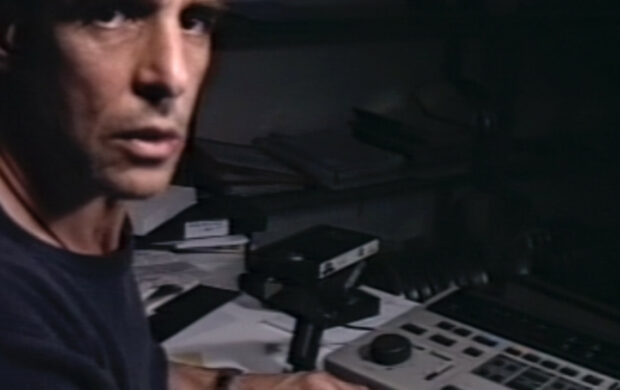

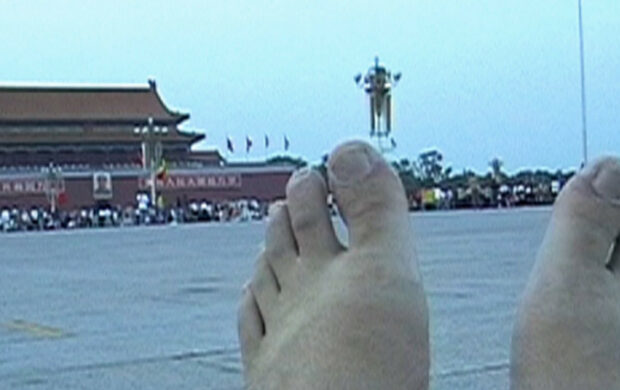

James Benning

James Benning’s preferred way of filming is alone, from life, and out in the open air.

From 1971 to 2007, he worked solo, using a Nagra and a 16 mm Bolex, before turning to digital and HD in 2009. While the length of his takes has tended to increase, the principles of his filmmaking — “Looking and Listening”, according to the title of his class at the California Institute of the Arts—have remained unchanged. A tireless explorer of the United States, he is as much a student in the art of contemplation as he is in the art of the motif. Random buildings, suburban wastelands, country roads, bustling factories, flags flapping in the wind, or characters engaged in mundane activities: by taking a fragmentary approach to the American territory and its vernacular heritage, Benning allows us to embrace it in its entirety.First invited to Cinéma du Réel in 2018, when his film L. Cohen earned him the Grand Prix, Benning has returned to the festival twice, presenting THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA in 2022 and Allensworth in 2023. This year, the festival wished to throw light on the entirety of his work. In the same way that the 2021 film THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA revisited the title of one of his most iconic films from the 1970s, we asked Benning to revisit his career according to one rule: each older film would have to be matched with a recent one, each film shot on celluloid with a film shot in digital. The aim of this was to allow the filmmaker to share his own experience of his work, while leaving it up to viewers to identify both changes brought on by the shift—evolutions in the rigor and in the simplicity of the set-ups—and clues tying each film back to Benning’s larger body of work.

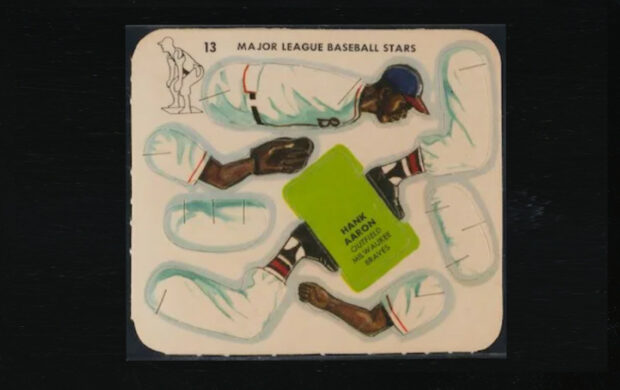

Asking James Benning to curate this programme according to a (minor) constraint was not accidental. Like the literary games of the Oulipo collective, each of his films is informed by a specific rule: 52 still shots, one for each American state, in the 2022 film THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA; a series of shots filmed through the windscreen of a car travelling from New York to Los Angeles in the 1975 version. Whereas the rule, which changes each time, sets a framework, the crucial experience proposed by the filmmaker remains unaltered: an experience of time and space, requiring both patience and an ability to let oneself be overcome by images and sound, or to give in to sensation. It is an experience of landscape as action. Over time, subtle and minimal variations in events, captured by Benning’s camera, reveal the geological and political story of America contained in the landscape: its history of violence and its popular culture.

Catherine Bizern

-

11 x 14

James Benning

-

13 Lakes

James Benning

-

American Dreams (lost and found)

James Benning

-

BREATHLESS

James Benning

-

Discussion with James Benning

-

Four Corners

James Benning

-

John Krieg exiting the Falk Corporation in 1971

James Benning

-

Landscape Suicide

James Benning

-

O Panama

James Benning

Burt Barr

-

READERS

James Benning

-

Ruhr

James Benning

-

SAM

James Benning

-

Stemple Pass

James Benning

-

two moons

James Benning

-

The United States of America (1975)

James Benning

-

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (2021)

James Benning

-

-

-

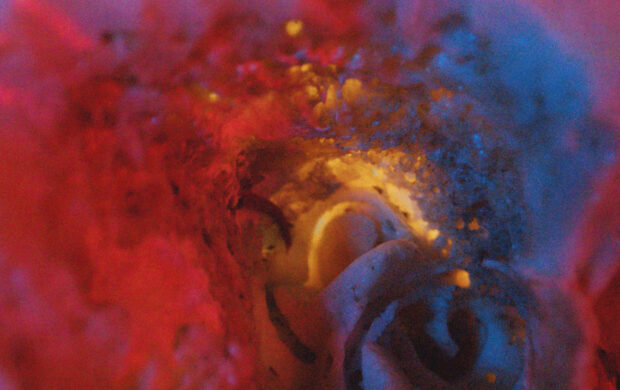

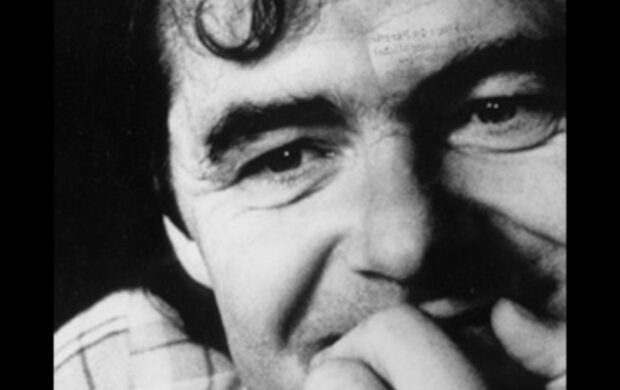

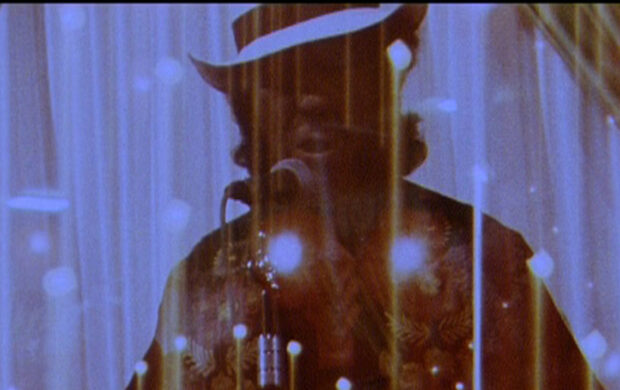

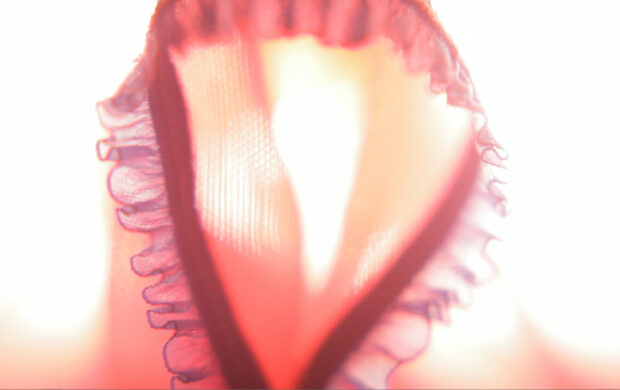

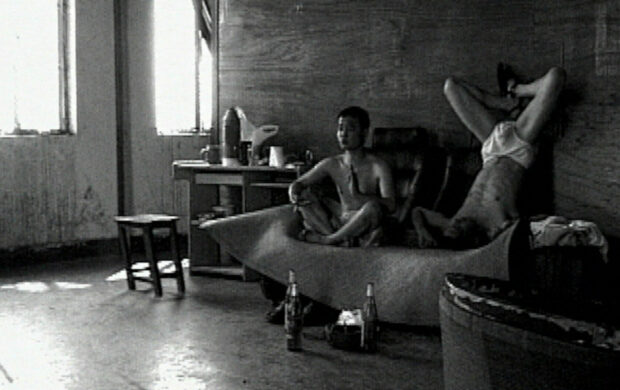

Jean-Charles Hue

It was at the Paris-Cergy National Graduate School of Art, in the film studio then run by Patrice Rollet, that Jean-Charles Hue, using the simple dispositif of direct cinema, explored the possibilities of what could be described as cinema in the raw. Ever since his first films, he has sought to film the vibration of bodies, with the camera embedded amidst the chaos of action, which he tries not only to record but also traverse. A camera that is also wild-eyed, trying to look directly into the light, to the point of blindness. Moving through what is conspicuous to reach its very heart, a place where another image emerges, like an epiphany. Be it with the Dorkels, a Yenish family settled in Pontoise, or with outcasts in Tijuana, his films are a territory shared between fiction and documentary, the true and the legendary, between light and darkness, between life and death. His camera always balanced on the threshold, in between.

The story forged by all the films made with the Dorkels – La BM du Seigneur and Mange tes morts, together with all his preceding shorts – is an adventure story in which, like the pure western classics, love, faith and violence build the legend. More than anyone else, Fred Dorkel is this real character caught “legending in flagrante delicto”¹ and through whom the image of an entire people comes to cinema. Filming the Dorkels, making films with them also means sharing their life, camping on the border between art and life. In Tijuana, it is on this same border that Jean-Charles Hue stands. He roams the city streets and, far from the trendy districts, films underworld characters whose daily life is mainly taken up by drugs, violence and prostitution. His camera sticks tightly to the state of these protagonists, between wanderings and trance, and films with kindliness, whether they are eating, quarrelling, smoking crack or flipping into a parallel world. The camera then escapes into fantasy, pearls and trinkets glisten like treasures, bodies rejuvenate, floating under veils of colour. When filming these ravaged men and women, the filmmaker tries his utmost to capture the vibrant imprint of these people’s intensely fragile life, as if to hold onto it or restore its materiality.

Hue’s cinema could be viewed as desperate, but it is driven by belief, a belief in the ability of some to abandon themselves to extreme states, plunge into an unreal and hallucinatory space-time, to the point of deserting the world of mortals, then miraculously returning… The belief in a haunting and dreamlike beauty dragged out of the mire in a state of grace that is beyond chaos.Catherine Bizern

_____

¹To use the expression of Pierre Perrault and the ideas of Gilles Deleuze.

-

Un ange

Jean-Charles Hue

-

La BM du seigneur

Jean-Charles Hue

-

Carne viva

Jean-Charles Hue

-

DISCUSSION WITH JEAN-CHARLES HUE

-

Emilio

Jean-Charles Hue

-

Mange tes morts - Tu ne diras point

Jean-Charles Hue

-

La mort vient sans prévenance

Jean-Charles Hue

-

L'Œil de Fred

Jean-Charles Hue

-

Perdonami mama

Jean-Charles Hue

-

Pitbull carnaval

Jean-Charles Hue

-

Quoi de neuf docteur ?

Jean-Charles Hue

-

The Soiled Doves of Tijuana

Jean-Charles Hue

-

Tijuana jarretelle, le diable

Jean-Charles Hue

-

Tijuana Tales

Jean-Charles Hue

-

Topo y Wera

Jean-Charles Hue

-

Y a plus d'os

Jean-Charles Hue

-

-

-

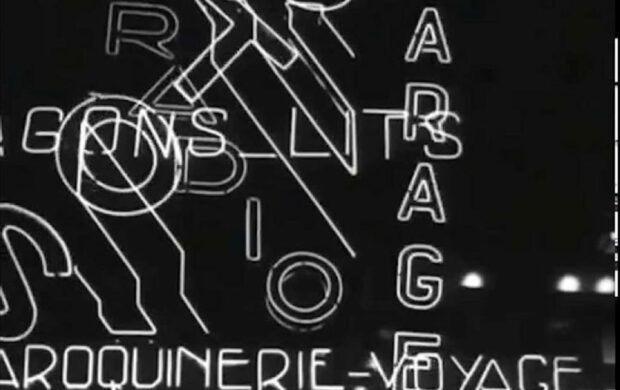

A whole night: Tribute to Marie-Pierre Duhamel

A great programmer who excelled at passing on her love of films, Marie-Pierre Duhamel was General Delegate of Cinéma du réel from 2005 to 2008—and much, much more. The festival pays tribute to this guiding force through a selection of films reflecting Marie-Pierre Duhamel’s tastes and finds. A night dedicated to remembering an inspiring figure, her great knowledge, her wit, and her curious mind.

On the night of Saturday 30 March to Sunday 31 March, from 7.30pm to 8am.

The night ends with a complimentary breakfast for the audience. -

A Day to Remember

Wei Liu

-

Besitzbürgerin Jahrgang 1908

Alexander Kluge

-

Between the Devil and the Wide Blue Sea

Romuald Karmakar

-

Broadway by Light

William Klein

-

El cielo gira

Mercedes Álvarez

-

La Fabrique du Conte d'été

Françoise Etchegaray

Jean-André Fieschi

-

Frau Blackburn, geb. 5 Jan. 1872, wird gefilmt

Alexander Kluge

-

Geschichte der Nacht

Clemens Klopfenstein

-

Gita Govinda

Amit Dutta

-

Images d'Orient, tourisme vandale

Yervant Gianikian

Angela Ricci Lucchi

-

Meng you

Huang Wenhai

-

Nocturne

Emily Richardson

-

Les Nuits électriques

Eugène Deslaw

-

Several Friends

Charles Burnett

-

Venise n'existe pas

Jean-Claude Rousseau

-

-

-

Festival conversations

Common, Commons

In the past, commons were land that belonged to no one and was used by all so that everyone could live off the fruit of their labour. Starting in the 17th century, commons began to vanish, wiped out by reforms that allowed the Church and the nobility to snatch up the land. This was the starting point of capitalism.

Since time immemorial, fights for the preservation of commons, access to vital resources, and the defence of shared spaces have shaped the history of political struggles, some of them resulting in victories, including in France, in the 1970s Larzac, or more recently, at Notre-Dame-des-Landes. In addition to common goods (which include water, land, forests, and threatened farmland), negative commons (such as landfills, contaminated soils, nuclear plants, Anthropocene-related waste) also call for a collective approach.

To take up the notion of commons is to stand up for the collective interest instead of proprietary logics. It’s also about fostering social relations defined by collective management and a politics of sharing: it’s about working in common, passing on and pooling tools as well as knowledge and practices.

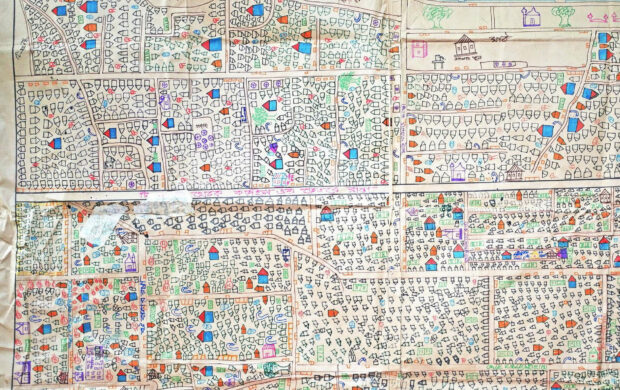

During the fifth edition of Festival Conversations, cartographers, writers, historians, philosophers, filmmakers, and activists are invited to consider not only the spaces, resources, and histories that we share, but also the practices, knowledge, and imagery that may provide an alternative to prevailing narratives.

Each year, Editions de l’œil publishes a book based on Festival Conversations. Festival Conversations#4, which explored the notion of event in 2023, will be released in March 2024

-

FORMES COMMUNES

-

L’HORIZON DES COMMUNS

-