Édition 2021

-

-

International Selection

21 films: 11 feature films, 10 short films.

-

A River Runs, Turns, Erases, Replaces

-

Armour

-

Citadel

-

earthearthearth

-

End of the Season

-

Faraway My Shadow Wandered

-

Feast

-

Figure Minus Fact

-

The Filmmaker’s House

-

Flowers Blooming in Our Throats

-

FREIZEIT or: the opposite of doing nothing

-

The I and S of Lives

-

The Inheritance

-

Landscapes of Resistance

-

Patrick

-

Les Prières de Delphine

-

Rock Bottom Riser

-

Sol de Campinas

-

Taming the Garden

-

Tellurian Drama

-

-

-

French Selection

20 films in world premiere: 9 feature films, 11 short films.

_____

-

Avant que le ciel n’apparaisse

-

Baleh-baleh

-

Corps Samples

-

Dear Hacker

-

Désir d’une île

-

L’État des lieux sera dressé à onze heures en présence de la femme du poète

-

Foedora

-

Garage, des moteurs et des hommes

-

Incandescence des hyènes

-

Ivre de soule

-

Kindertotenlieder

-

Living with Imperfection

-

Random Patrol

-

Saxifrages, quatre nuits blanches

-

Silabario

-

Un mal sous son bras

-

Un monde flottant

-

Un souvenir d'archives

-

VENICE BEACH, CA.

-

-

-

Special Screenings

-

The New Gospel

-

Nous

-

Ziyara

-

-

-

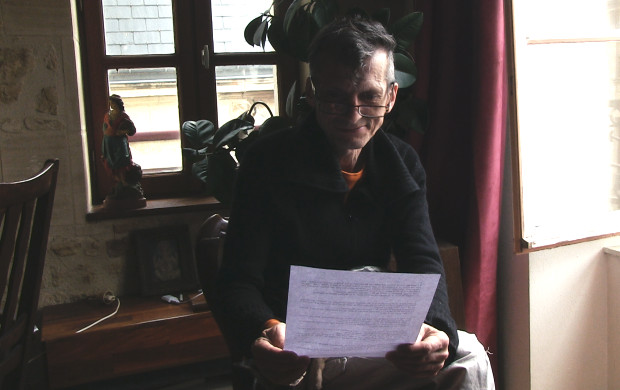

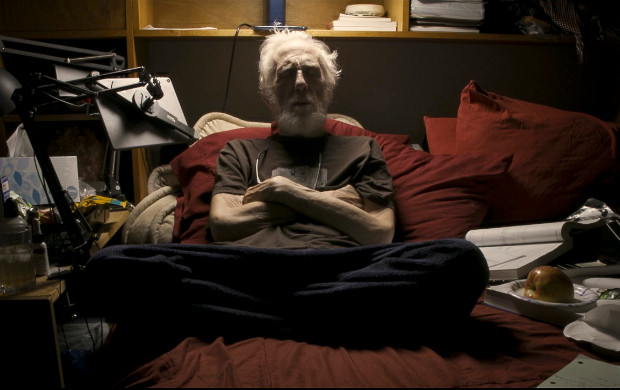

Pierre Creton

At the heart of Pierre Creton’s cinema, is first and foremost the encounter. With beings, places, readings, events and the singular experience of a man living amongst the living, determined to be together. Between living and doing, the films are woven. Acting, feeling, desiring. Films sustained by the lyricism and sensuality of gestures and bodies, as much as events and action. The combination of Pierre Creton’s life and filmmaking is central to his oeuvre and to the creative alchemy that leaves its mark on all of his films. This combination is the material for each film and dictates their form.

It is with deep emotion that, on seeing Pierre’s first films again, I recognise the formal attempts, the narrative principles, and images, some of which will grow stronger while others will nurture recurrent and more or less direct variations. But also, from one film to another, entering into an intimacy, a circle of well-meaning friends where each living being takes care of the other and the surrounding world. People, animals, cliffs, roads and fields… We can imagine Pierre Creton as a surveyor of his familiar territory but also of a cinematic territory whose expansion in concentric circles we experience on discovering the totality of his films.

Creton, a surveyor rooted in his ground, has an acolyte, Vincent Barré; Vincent is the one who leaves, travels afar, sometimes dragging Pierre along with him, as infrequently as possible so it seems. Yet, it is as a twosome, in their exchanges of news from both near and far, in an attentive sharing of a permanent “here”, that the story, the experience and the fiction of the world are conveyed to us.

Catherine Bizern

_____

-

Le paysage pour témoin. Rencontre avec Georges-Arthur Goldschmidt

Pierre Creton

Vincent Barré

-

Aline Cézanne

-

L'Arc d'Iris, souvenir d'un jardin

-

La Cabane de Dieu

-

Côté jardin

-

Deng Guo Yuan, in the garden

-

Détour, suivi de Jovan From Foula

-

Dialogue de l’arbre (Carte postale à Pierre Creton)

-

L'Heure du Berger

-

L'avenir le dira

-

La Vie après la mort

-

Le Bel Été

-

Le Grand Cortège

-

Le Vicinal

-

Le Voyage à Vézelay

-

Les Jardiniers du Petit Paris

-

Maniquerville

-

Le Marché, petit commerce documentaire

-

Mercier et Camier

-

Mètis

-

Papa, maman, Perret et moi. Un appartement pour témoin

-

Paysage imposé

-

Le paysage pour témoin. Rencontre avec Georges-Arthur Goldschmidt

-

Petit traité de la marche en plaine

-

Secteur 545

-

Sept pièces du puzzle néo-libéral

-

Simon, At the Crack of Dawn

-

Soleil

-

Sur la voie critique

-

Une saison

-

Va, Toto !

-

Les Vrilles de la vigne

-

-

-

Filmmakers in their garden

Cultivating: bringing forth and letting grow

If the farmer cultivates, so does the artist. And rather than opposing work on the land to intellectual and creative thought – as does a certain Western tradition –, we should view them as extensions of each other, the two ends of the same universe which some filmmakers have chosen to keep close, very close together. They thus doubtless conceive their being-in-the-world in an alternative way, cherish the connections between the forces that shape landscape and creative work. By devoting their life to both garden and cinema, they are not exercising two metiers but busying themselves with living, being alive.

It is no coincidence that, in the works of these filmmakers – Rose Lowder, Sophie Roger, Robert Huot or Hilal Baydarov – we find the same thread of interdisciplinarity that is common to working in the fields and gardening, as well as poetry, performance and repetition, which all construct another temporality for the gaze, a sensory world closely linked to the world around.

In choosing the countryside as a place of life and cinema, these filmmakers transform their everyday setting into the studio where they can practice their art, the garden of their thoughts, their preoccupations, their joy or their difficulty in living, and the wellspring of their relationship to the other and their understanding of the world. It seem that their gaze, when it tarries on trees, flowers and animals, probes the depths of their being and, in this way, they create something akin to a self-portrait.Catherine Bizern

Read Land Cinema, Life Certificates by Becca Voelcker

_____

-

As I Was Moving Ahead, Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty

-

Dialogue de l’arbre (Carte postale à Pierre Creton)

-

E agora ?

-

Les Jardiniers du Petit Paris

-

L'Île déserte

-

Margaret Tait

-

Notes 1984, Part.3

-

Le Point Aveugle

-

Rolls : 1971

-

Rose Lowder

-

-

-

Popular Front(s) - What use are citizens?

In November 2020, the national health emergency is in force. We are in lockdown, remote working is the rule and the only chance we have to bump into neighbours, colleagues and people we know are in places selling essential goods. This is the precise moment, when everyone has nothing to do but produce and consume, that the French government chooses to push through the so-called “National Security” law, which bolsters the control and surveillance mechanisms functioning in our democracy.

What we see – in a blatant, even caricatural manner – is the practical application of a remark made by Gabriel Tarde, the founder of social psychology: to reign without any opposition, political power has simply to eliminate all the places where people discuss, and introduce a “universal mutism”. Covid-19 has shaken up our work habits and conviviality, our patterns of consumption and, so it seems, our democratic achievements. So we felt that it was more than urgent to ask the question, through films and filmmakers’ initiatives: “What use are citizens?” and again discuss how all of us can not just debate, but also decide.Why should society only follow and adapt, as if citizens were no more than recipients of policies and measures to be respected? As adults, citizens, we are able to implement modes of direct actions that can influence the decisions of those who govern us, able to question our society and tackle its injustices. And the sum of these injustices, our indignations, violence against the poorest, migrants, the vulnerable, the young, and which concern all of us, now seems to be increasing exponentially.

So to brave fatalism, spread positive experiences, nurture future combats and celebrate victories, this year’s Popular Front(s) programme tarries on our role of citizen, the one we are prepared to assume and the one that we could seize.

Catherine Bizern

_____

-

A lua platz

-

For a Manifest Hospitality

-

Her Socialist Smile

-

Inside the Red Brick Wall

-

Rêve de Gotokuji par un premier mai sans lune

-

Who Is Afraid of Ideology ? (Part. I, II, III)

-