Tout l’or du monde

End of the Rainbow

- 2007

- France; Australia

- 83 minutes

- French; English; Malinke

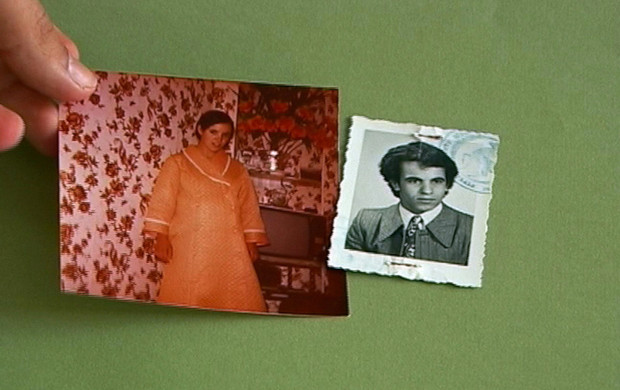

Tout l’or du monde is above all a contrasting portrait of two men: an elderly engineer, close to retirement, who loves his job and has no future plans, and an old griot intent on handing down the truth of his land. One has succeeded professionally but failed in his personal life, the other in perpetuating his world. Gold does not buy happiness, any more than money. The film compares two irreconcilable relationships with gold: the West’s materialism and greed, and Africa’s traditions and spiritual values. “God created gold, but the Whites know how to use it. The Blacks don’t. We only know how to admire it. The Whites know its value and importance on earth and beyond.” What the film portrays is not so much a confrontation between Blacks and Whites, poor and rich, farmers and industrialists, village and technology, as capitalism’s chronic inability to understand anything different from itself. In Borneo or Guinea, the company behaves in the same way, with the same utilitarian relationship with the land. The mining company sees itself as ecological and socially responsible, protecting the environment and bringing progress to the land it contaminates. Yet it is unaware of the growing discontent of farmers, who are forced off their land: roads cut, which prevents them accessing their fields; gold-washing prohibited, with disastrous consequences for their families; no hiring of farmers on the work sites and no redistribution of work or wealth. The company fails to appreciate the extent of the changes its presence causes. The villagers speak of the end of a world, undermined by poverty and the lure of profit: “Before, we used gold for jewellery. Today, thieves would even cut off your ears… Our protective spirits have abandoned us.” (Yann Lardeau)

- Production : Looking Glass Pictures; Trans Europe Film

- Distribution : Doc & Co

- Editing : Andrea Lang

- Sound : Erik Ménard

- Photography : Robert Nugent; Laurent Chevallier