The Raw and the Cooked

Co Mo Li

- 2022

- Taiwan

- 28 min

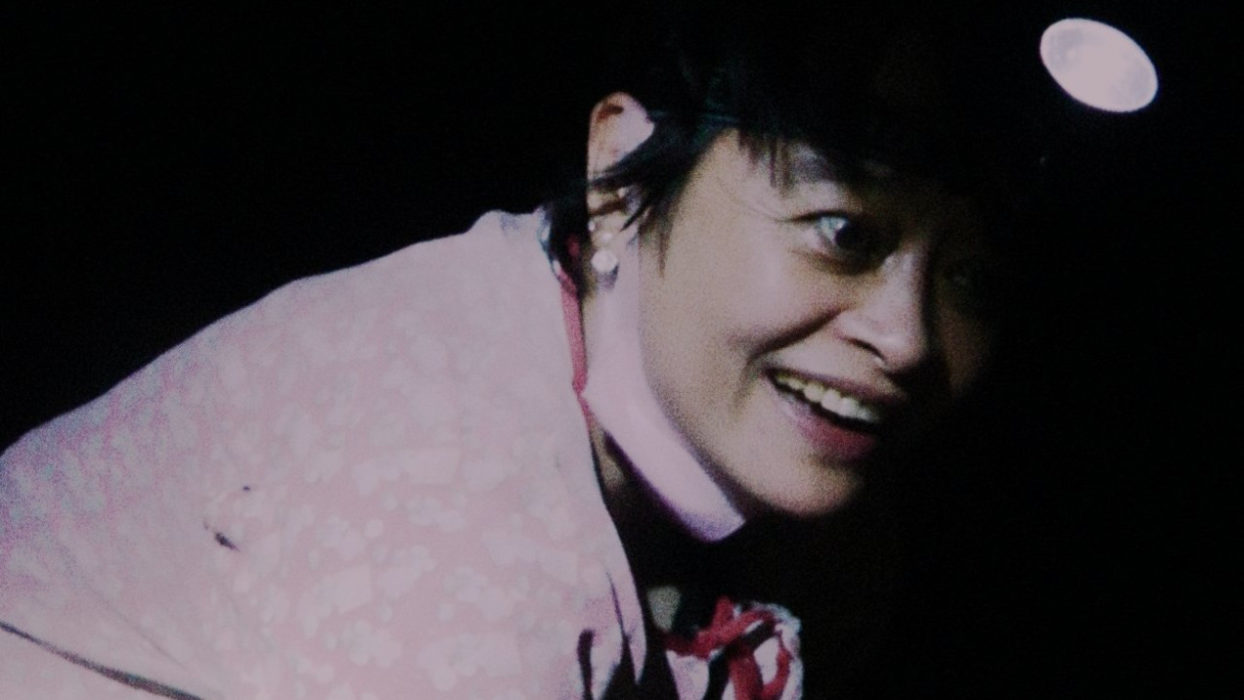

The Chens are an Amis family on Taiwan’s eastern coast. As some family members venture into the brush after a midnight rain, others harvest rice amid the whir of machinery. Blending work and play, food becomes a site for the Chens to pass down their endangered language to a younger generation, trade ghost stories, and express the vibrant hybridity of contemporary indigenous identity.

On the Taiwan coast, in the depths of a wet night lit by unsteady telephone torches and a few headlamps, a family is hunting for black snails and white snails. The camera nimbly tracks the hunters, who plunge into the darkness in search of the slow-moving gastropods. Snails fly from all sides, wobble on bucket rims and fall in. Filmed with a 16 mm camera as wide-awake as the hunters, the hunt is filmed in bursts and brief impressions. The filmmakers play on changes of scale, switching from the tracker to the tracked. The humidity of the high grass mingles with the slimy trails of their slow defenceless prey. White snails, black snails, we learn that the black are less tasty. A surprising discrimination heard as a snatch of the intermittent discussions that waft from the family house after the hunt. The conversations continue into the kitchen, watching the creatures boil, sweat, go from raw to cooked. The camera hovering over the cooking pot and plunged in steam witnesses the final moments of the catches. The discussions paint a new portrait, we learn that the family of hunters is an aboriginal Taiwanese family. And so the story of the community is told. Other discriminations, other traces suddenly emerge. Then come the stories of apparitions, ghosts and beliefs passed on by the elderly. The disappearance of men and women, but also their traditions.

Clémence Arrivé

- Producer, Cinematography : Lisa Marie Malloy

- Screenplay, Sound, Editing : Dennis Zhou, Lisa Marie Malloy

- Print source : lmm324@cornell.edu