Édition 2023

Each year, Cinéma du réel ponders upon the state of the documentary, its forms, its developments and the approaches of its filmmakers. This is what lends the festival its exploratory side, making it an ongoing research project. In addition to the screening of this flourishing contemporary international documentary cinema, Cinéma du réel invites us to experience the world and cinema through a plethora of gazes on the world, a plurality of documentary practices and visions other than our own. Because cinema passes from the filmmaker’s mind to the mind of the spectator, it is an art of connivance, even collusion, between filmmaker and spectator, who experiences another imaginary, a universe other than his or her own. But this experience – which is also that of the other or rather the distance separating him or her from me – is singular inasmuch as it also reminds us that we all inhabit the same world. A world to watch without being blinded by the continuous flow of events. And it is perhaps through films that disturb, upend imaginaries, confront other desires, other aspirations, other dreams, that a discontinuity occurs in the inexorable unfolding of real-world events. This discontinuity, which questions, surprises, resists, delights, is what helps us to avoid being blinded and to look at our contemporaries. This is our invitation to the audiences of Cinéma du réel. Catherine Bizern

-

-

-

-

-

-

The World, differently / Franssou Prenant

-

BIENVENUE À MADAGASCAR

Franssou Prenant

-

DE LA CONQUÊTE

Franssou Prenant

-

DISCUSSION WITH FRANSSOU PRENANT

-

L’ESCALE DE GUINÉE

Franssou Prenant

-

HABIBI

Franssou Prenant

-

I AM TOO SEXY FOR MY BODY, FOR MY BO-ODY

Franssou Prenant

-

LE JEU DE L’OIE DU PROFESSEUR POILIBUS

Franssou Prenant

-

PARADIS PERDU

Franssou Prenant

-

PARIS, MON PETIT CORPS EST BIEN LAS DE CE GRAND MONDE

Franssou Prenant

-

REVIENS ET PRENDS-MOI

Franssou Prenant

-

SOUS LE CIEL LUMINEUX DE SON PAYS NATAL

Franssou Prenant

-

-

-

The World, differently / Olivier Zabat

And comprehension is exactly what is being questioned: what do Mirek and Yves comprehend of the world, how do they experience it, both in their life and in this sober, attentive frame in which Zabat places, observes and listens to them at great length? What is comprehended by someone who is a mine clearance expert and whose gestures expose him every day to the possibility of nothingness (Miguel et les Mines, 1/3 des yeux)? What does someone who indeed never stops hearing, is weary of hearing, because he is a “voice-hearer” (Arguments), or someone whose sensitivity and belief have convinced him that he is surrounded by the murmurs of the dead (Fading)? Just as Yves was not an essay on autism, Arguments makes no attempt to document psychosis, and it is telling that the film was for a time titled Percepts. In fact, nothing interests Olivier Zabat’s films apart from envisaging this point of contact through which the character perceives the world, in the dull violence of a punch (we meet numerous boxers, wrestlers, fighers of all kinds) or on the fuzzy border of an invisible continent (ghosts, “voices”).

A few motifs, here and there, clearly point to the intensity of this point of contact. In Arguments, a limpid shot captures the reflection of a voice-hearer in his apartment window as he looks out and describes the outside world: the silhouette of the trees on the horizon, the illuminated ballet of cars at dusk and, then, as he slowly detaches his perception from the viewer’s, the sound of the voices that torment him and that he alone hears, the voices lying “below the surface”, as another protagonist suffering from the same ailment later remarks. In Yves, the admirable idea of using condensation as a screen in the very first scenes epitomises not only the mystery of the character’s blurred perception but also the haze that his disability lays over the viewer’s comprehension. And of course, the most telling – and literally surgical – image of all, in 1/3 des yeux: the structure of an eye – at the same time, a fragile membrane, an open window and a screen.

This constantly recurring screen is of course a nod to cinema itself and, given the films’ often enigmatic weft, it encourages purely conceptual readings. Yet, this would mean, if not going down the wrong path, at least missing the essential. Firstly, because Olivier Zabat’s films, driven above all by the attention they give to their protagonists, do not strictly speaking belong to “dispositif” cinema, nor do they try to dissipate their subjects’ mystery through formal experimentation. The misunderstanding here is fuelled by the unique place occupied by the filmmaker, whose films are, shamefully, rarely shown in film theatres but have more than once found their place in art galleries. Their fragmentary nature lends itself well to such venues, as stand-alone segments can be readily extracted. The key, however, lies in the continuity between these segments: just as the investigation is oriented towards the point of encounter between the protagonists and their environment, the effect produced by the films relies for the most part on these intentionally cryptic articulations which, without warning, switch from the words of a boxer to those of a jigsaw enthusiast (Miguel et les mines), from a conference on language to a boxing match (1/3 des yeux), from a church wedding to a clandestine motorbike race (Fading).

This modular aspect, more (1/3 des yeux) or less (Arguments) pronounced depending on the film, plays a key role in the very particular and rather paradoxical sensitivity of Zabat’s films. Here is a cinema clinging to reality in ways that are a little crude, a little akin to poor art, almost sullen, fascinated by abysses and strength, most often inclined to film men (especially the proletariat, men with big hands, swollen by factory work and boxing), but nonetheless strangely gentle, always loving, obsessed with the invisible, totally poetic – a contradiction that brings it close to the work of one filmmaker, Werner Herzog, whose influence Zabat readily affirms.

The poetry, here, hangs almost entirely on the editing. The unwarranted connections between these blocks of reality create discreet sparks, imperceptible short-circuits, which dig new underground galleries for comprehension. The sequences in Zabat’s films interact like drifting islands, or a cloud of atoms, inviting the viewer’s sensitivity to shape their arrangement. But, even though the viewers are required to participate, the editing confronting them still respects the rules of meticulous composition and shows a concern for balance, as attested by the filmmaker’s well-known habit of re-editing his films after their first screening – removing a block here, adding a sequence there – for instance, the opening wedding scene in Fading, which appeared in the editing in between its first screening at the Venice Film Festival and a second at Belfort Festival. The behaviour of an obsessive sculptor (or painter, why not: Bonnard would even come to touch up his paintings in the museums), exhaustively kneading his raw material in the search to find there the path of the invisible.

This path, always unpredictable, never clearly identified by its form, is the splendour of Zabat’s films, where an unexpected emotion akin to vertigo always surges up. It is startling that a film like Arguments manages to accompany the literally fantastic perception of the voice-hearers as far as it does, without the slightest aesthetic strong-handedness. To achieve this, all that was needed (but this simplicity is, of course, only apparent) was for the film to become wholly absorbed in the description the voice-hearers give of it, and even find there the rules for its mise en scène. For, here, cinema never appears as an extra touch of sensitivity: it is always the protagonists’ words that shape and dramatize the space.

Fading thus promises us an incomparable experience, drawing on a unique quality (the deeply moving trust and friendship binding the film to its characters) to find the necessary resources to join the ghosts on the other side of the bridge. Deep in the shadowy basements of a psychiatric hospital where the security guards Marco and Verlisier are doing their night rounds, the two young men are convinced they have detected a presence, some hostile spectre recognised in a vague brilliance or distant murmur. They ask Zabat to record the traces of these apparitions and, in return, the filmmaker invites them to re-enact in the same basements the terror of their discovery. Here the feverish and childlike belief of the two characters is met by a symmetrical act of faith from the film, which is determined to espouse their anxious perceptions and use them to reshape the experience in the mundane settings around which Marco and Verlisier, like storybook heroes, lead us. Fiction in a documentary in a fiction – no matter, just as it barely matters whether the viewers see or not the ghosts that terrify these two marvellous characters: in the incredible arrangement that the film offers them, they will have tracked reality into the chasms that few films are able to find the way to.

Jérôme Momcilovic

[1] The French term “entendement” denotes the faculty to understand the meaning of something; all of the intellectual faculties – intelligence, reason. In this text, the English translation “comprehension” is used. See the interview at http://www.elumiere.net/exclusivo_web/bafici11/bafici11_07.php

-

1/3 DES YEUX

Christophe Cognet

-

L'AGRESSION

Christophe Cognet

-

ARGUMENTS

Christophe Cognet

-

LE BRUIT

Christophe Cognet

-

CE QUE DIT MA MÈRE

Christophe Cognet

-

FADING

Christophe Cognet

-

LA FEMME EST SENTIMENTALE

Christophe Cognet

-

KIDDING

Christophe Cognet

-

MIGUEL ET LES MINES

Christophe Cognet

-

MIGUEL ET LES MINES

Christophe Cognet

-

LES MOTS DE LA PLUIE

Christophe Cognet

-

NE ME TOUCHE PAS

Christophe Cognet

-

OLIVIER ZABAT - DISCUSSION COLLAGES 1

-

OLIVIER ZABAT - DISCUSSION COLLAGES 2

-

OLIVIER ZABAT MASTERCLASS

-

PERSPECTIVES DU SOUS-SOL

Christophe Cognet

-

SILENT MINUTES

Christophe Cognet

-

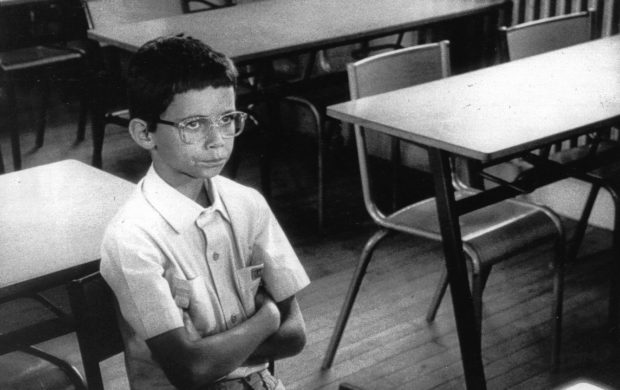

YVES

Christophe Cognet

-

ZONA OESTE

Christophe Cognet

-

-

-

The World, differently / Jean-Pierre Gorin

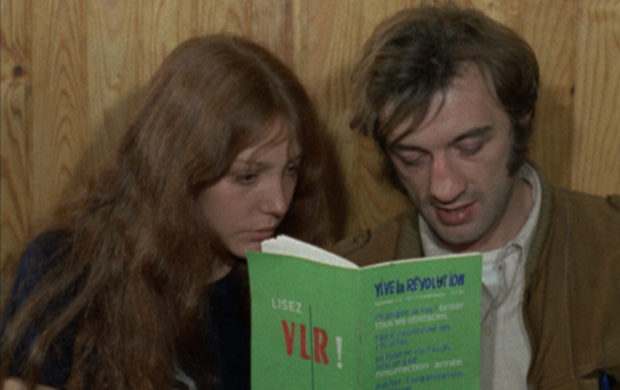

In the wake of May ‘68, Jean-Pierre Gorin, an activist in the Marxist-Leninist Communist Youth movement, took up filmmaking rather than go into politics and teamed up with Jean-Luc Godard; together they created a collective – the Dziga Vertov Group – which aimed to “make political films politically”. The group stood out from the other political collectives proliferating at the time (Medvedkin Group, L’ARC, Cinélutte, etc.) on account of a cinematic practice that could be described more as essay film than militant cinema. In each film, the goal was to challenge cinema as a system and a narrative – and to make this challenge visible. For the Dziga Vertov Group, filmmaking is a secondary task but the main activity – a device that serves to develop a questioning.

Between 1969 and 1974, six films were made – and many unfinished projects launched. The best-known and last, Everything’s All Right, featuring Jane Fonda and Yves Montand, is signed Godard-Gorin and produced by the young producer Jean-Pierre Rassam.

Opposing the tyranny of the narrative, these films are enraged, radical, caustic and ultimately burlesque. Emblematically, it is Vladimir and Rosa – undoubtedly the most Maoist-slapstick comedy ever made – that Jean-Pierre Gorin has chosen to show today and about which he wrote in 2004: the juxtaposition of strident voices, the actors’ appalling “non-acting”, the “revolutionary” parodies, each more idiotic than the others, anticipate the best of punk and hip hop. In this film, where Gorin and Godard play the fool and where the subversive pleasure of comedy upends the taste for theory, it is farce that has a revolutionary virtue, in this grating attempt to turn the spectacle against the powers that be.This is the spirit in which Jean-Pierre Gorin invites us to revisit all the films made by the Dziga Vertov Group: These films have been seen by three people including two enthusiasts… A guided tour of the Dziga Vertov Group, the title of his conference is not simply a matter of coquetry. It highlights the confidentiality of the films’ distribution. Screened on the fringes of mainstream cinema, the films were rebuffed by leftist activists of all stripes, save a handful of aficionados mainly in the United States (cf. Jean Paul Fargier’s testimony in Cahiers du cinéma, October 2022). Rejected by both the film industry and most critics were scornful of the approach of the Group – who gave like for like. Rejected at times by Gorin and Godard themselves who admitted failure, but also the contradiction, the impasse even, in which their imperative to be both political and cinematic had led them. Receiving no or very little recognition, their mode of production itself deprived the films of any visibility: the television networks and distributors (Italian, German, American) that commissioned them, drawn merely by Godard’s name, refused to broadcast them after seeing the final result, while still holding on to the exploitation rights. Apart from Everything’s All Right, which was theatrically released, the films remained unseen at the time. Today, Gaumont holds their exploitation rights.

It was painter and film critic Manny Farber who invited Jean-Pierre Gorin to the United Stated in 1975 to teach film studies at San Diego University, where he currently lives.

Between 1978 and 1992 Jean Pierre Gorin made three films, usually referred to as his Californian trilogy.

These three films all experiment with the ways a community forms, each film being characterised mainly by its language: the language that Poto and Cabengo invent to communicate together, the coded language full of imagery used by the street gang in My Crasy Life, the specialist language spoken by the model-train devotees in Routine Pleasure… in each case, with the desire to join in, the characters’ desire, but above all the desire of Gorin himself. Join in with this duo of twins that he desperately tries to contain within his frame, join in with the Samoan street gang that he accompanies on vacation to Hawaii, join in with this club of elderly Americans who, every Tuesday in their hangar, have the whole of America spread out before their eyes.

Jean-Pierre Gorin the filmmaker is not fooled by the desire to join in with his double, Gorin the narrator. He watches him from a kindly yet mocking distance as his double tries to figure out how to exist in the filmic space. Each time, this space is one of encounters, a playground and childhood’s territory. At the very least, a possible place for a vacuum-like state shared with shared with the two twins who enjoy being the centre of attention, with the gangsters who once away from home drop their violent stance for a little light-heartedness, with these elderly children who play with electric trains and the great American saga.

In this vacuum-like state , the filmmaker also accepts that he doesn’t quite master his subject or rather plays at letting himself be overwhelmed by it… doubtless a way of pursuing the attempt to jam the staged machine, and a way of being there, of course, but being there differently, in a kind of detachment, the kind that prompted the Dziga Vertov Group to say: filmmaking is a secondary task, but the main activity.

Don’t we find in these American films the same ingenuousness that seeks to open eyes and show the world as the one we see in the films of the Dziga Vertov Group? In particular, the same belief and the same attachment to the origins of cinema, as shown by Gorin’s choice for his carte blanche. Two films alongside Poto and Cabengo: En rachâchant by Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub and Ozu’s I Was Born, But… and two films about the American myth: Griffith’s The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912) and Hawk’s Ceiling Zero (1935). The myth that Routine Pleasures and My Crasy Life embodied perfectly.Catherine Bizern

-

CEILING ZERO

Howard Hawks

-

EN RACHÂCHANT

Jean-Marie Straub

Danièle Huillet

-

I WAS BORN, BUT...

Yasujiro Ozu

-

THE MUSKETEERS OF PIG ALLEY

David W. Griffith

-

MY CRASY LIFE

Christophe Cognet

-

POTO AND CABENGO

Christophe Cognet

-

ROUTINE PLEASURES

Christophe Cognet

-

THESE FILMS WERE SEEN BY THREE PEOPLE, TWO OF WHOM WERE ENTHUSIASTS... A GUIDED TOUR OF THE DZIGA VERTOV GROUP

-

VLADIMIR ET ROSA

Groupe Dziga Vertov

-

-

-

The World, differently / 12 other perspectives

Antoine D’Agata

Pierre Creton

Amit Dutta

Gala Hernández López

Sharon Lockhart

Luis López Carrasco

Raya Martin

Ben Rivers and Ben Russell

Fern Silva

Total Refusal

Apichatpong Weerasethakul -

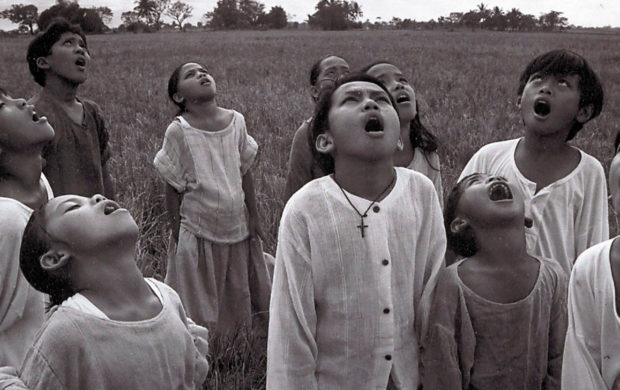

A SHORT FILM ABOUT THE INDIO NACIONAL

Raya Martin

-

A SPELL TO WARD OFF THE DARKNESS

Ben Rivers

Ben Russell

-

ATLAS

Antoine d'Agata

-

LA CABANE DE DIEU

Pierre Creton

-

THE FUTURE

Luis López Carrasco

-

HARDLY WORKING

Total Refusal

-

LE HORLA

Pierre Creton

-

HOUSE OF LOVE

Pierre Creton

-

LUNCH BREAK

Sharon Lockhart

-

THE MECANICS OF FLUIDS

Gala Hernández López

-

MEKONG HOTEL

Apichatpong Weerasethakul

-

NAINSUKH

Amit Dutta

-

RIDE LIKE LIGHTNING, CRASH LIKE THUNDER

Fern Silva

-

ROCK BOTTOM RISER

Fern Silva

-

-

-

-

-

-