Édition 2024

“Taking stock of documentary filmmaking as a cinema of mise-en-scene”: this was the idea that gave shape to this edition of Cinéma du Réel, along with the decision to showcase the work of three filmmakers from different corners of the cinematic map. First, with the first French retrospective dedicated to Claudia von Alemann, a pivotal figure of German feminist cinema and one unafraid to mix different languages and narrative devices. Ultimately, these varied approaches coalesce into a body of work that sits at the crossroads of political, shared and personal experience. Second, with the pioneering figure of independent US cinema, James Benning, an avid explorer of America and a keen observer of its history, whose explorations of the country’s storied and eventful landscape create an experience of time and space. Third, with Jean-Charles Hue, whose films, standing halfway between documentary and fiction, plunge us into the heart of a troubled, dangerous and intense reality, in company of the Yenish community in France and with the social outcasts of Tijuana. Documentary filmmaking spans a vast territory whose porous and changing borders allow for formal as well as narrative experimentation. The competition explores these manifold experimentations through a line-up of French and international productions, short- and feature-length, made by emergent filmmakers and acclaimed directors. Experimentation is also the through-line of First Window, a category dedicated to outstanding debut films put forward by a new generation of filmmakers. Popular Front(s) and Special Screenings complete this line-up of contemporary documentary films which investigate and provide new readings of the world we live in. Cinéma du réel also invites viewers to set out on an alternate, more anarchic, and less definite path. Like parts of a rhizomatic process, films complete each other, look at each another: Marie-Pierre Duhamel spoke of films as “holding hands”. Films reframe the tensions that run through our present, bringing out its rugged complexity, its friction, as well as what is in plain sight: the obvious persistence of colonial power experienced by the inhabitants of overseas territories, as shown by the films of Martine Delumeau and Malaury Eloi Paisley in Guadeloupe, by the films of Cécile Laveissière and Jean-Marie Pernelle in Réunion, and by the films of Florence Lazar in Martinique; and the obvious persistence of colonial power which gradually emerges from Mati Diop’s Dahomey, this year’s opening film. Colonialism is again at issue in Soundtrack of a Coup d’Etat, which draws a connection between the American Civil Rights Movement and independence struggles in African countries. It looms large in Raphael Pillosio’s Les Mots qu’elles eurent un jour, which centres on the story of women combatants during the Algerian War, beautifully portrayed by Yann le Masson upon their release from prison. The portrait of these modern and deeply committed women who fought for freedom in 1962 is a reminder that the fight against the patriarchy is neither new nor over. Feminism, if we so choose to call it, will also be at issue in the retrospective dedicated to Claudia von Alemann, and in the films of Claudine Bories, Natacha Thiéry, Sabine Groenewegen, and Kumjana Novakova, among others. Each of these screenings will offer a chance to reflect on the political experience of women filmmakers, on their work, and on their trajectories. And then there is Gaza: not as the event suddenly bursting into our lives and leaving us stunned, as if by some suspension of time, but as something happening to us all and reshaping the way we consider the present, human relations, and our relation to the world. What is happening in Gaza, at this very moment, informs the way we watch films: not only those coming to us from Palestine, but those from Sarajevo and from the Nagorno-Karabakh as well. Catherine Bizern

-

-

-

-

-

Popular front(s)

Films where the cinematographic gesture in the face of violence is that of a witness but also one that reconfigures the field of memory, a gesture of sharing new principles of intelligibility. Individually and together.

From the Christians’ commitment to political struggles in Latin America to the story of the Farcs’ reorganisation of the guerrilla in Colombia, we revisit the story of how the Latin American oligarchies use violence to hold onto their privileges. This struggle of the poorest for a harmonious coexistence is also found in the small activist community that set up at the roundabout in Le Tampon on Reunion Island. Here in France, walls are the rallying points for the struggle against the patriarchy, the urban space being more than ever claimed as a space of freedom and the affirmation of a collective revolt.

Throughout the programme, situations mired in the violence of war follow on from each other, creating a shot/reverse-shot effect or rather the dreadful propagation of a disaster that repeats itself. This reminds us of the words of Jean-Luc Godard in Our Music “Why Sarajevo? Because Palestine”. Today it is the story of the siege of Sarajevo and the ways in which filmmakers bore witness to this time that inevitably takes us back to Gaza and its population under the bombs, here and now. It is the images of the exodus of men and women forced to leave all their possessions and land in Nagorno-Karabakh, expelled by the Azerbaijani army that suddenly concretises the cruel scenes that we know the Gazans are living through.

The war in Palestine. The films we have chosen, one of which was shot just after October 2023 (No Other Land), documents what the Israeli military occupation means; they also recount the Palestinians’ combat against obliteration. What can cinema do? The question asked by Cahiers du cinéma in their February issue is also ours but is it not a question that each film raises in its own specific way and that it directs not at cinema but suggests that the viewer explore? Popular Front(s) endeavours to create the conditions for this exploration.Catherine Bizern

-

The First 54 Years - An Abbreviated Manual for Military Occupation

Avi Mograbi

-

La Concorde

Sylvestre Meinzer

-

Cosmocide

Nicolas Klotz

Elisabeth Perceval

-

Cries Tear Through The Silence

Natacha Thiéry

-

Far From Michigan

Silva Khnkanosian

-

The Gospel of Revolution

François-Xavier Drouet

-

Guerilla des Farc, l'avenir a une histoire

Pierre Carles

-

No Other Land

Basel Adra

Hamdan Ballal

Yuval Abraham

Rachel Szor

-

Point virgule

Claire Doyon

-

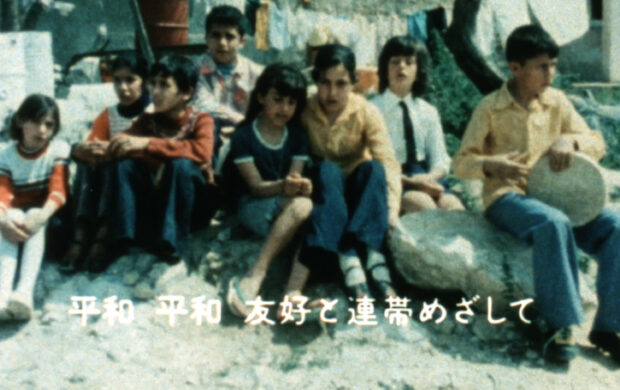

R21 AKA Restoring Solidarity

Mohanad Yaqubi

-

Se souvenir d'une ville

Jean-Gabriel Périot

-

Terla ta nou (Cette terre nous appartient)

Cécile Laveissière

Jean-Marie Pernelle

-

WHAT CAN THE CINEMA DO IN THE 21st CENTURY?

-

-

-

-

-

-