Édition 2024

“Taking stock of documentary filmmaking as a cinema of mise-en-scene”: this was the idea that gave shape to this edition of Cinéma du Réel, along with the decision to showcase the work of three filmmakers from different corners of the cinematic map. First, with the first French retrospective dedicated to Claudia von Alemann, a pivotal figure of German feminist cinema and one unafraid to mix different languages and narrative devices. Ultimately, these varied approaches coalesce into a body of work that sits at the crossroads of political, shared and personal experience. Second, with the pioneering figure of independent US cinema, James Benning, an avid explorer of America and a keen observer of its history, whose explorations of the country’s storied and eventful landscape create an experience of time and space. Third, with Jean-Charles Hue, whose films, standing halfway between documentary and fiction, plunge us into the heart of a troubled, dangerous and intense reality, in company of the Yenish community in France and with the social outcasts of Tijuana. Documentary filmmaking spans a vast territory whose porous and changing borders allow for formal as well as narrative experimentation. The competition explores these manifold experimentations through a line-up of French and international productions, short- and feature-length, made by emergent filmmakers and acclaimed directors. Experimentation is also the through-line of First Window, a category dedicated to outstanding debut films put forward by a new generation of filmmakers. Popular Front(s) and Special Screenings complete this line-up of contemporary documentary films which investigate and provide new readings of the world we live in. Cinéma du réel also invites viewers to set out on an alternate, more anarchic, and less definite path. Like parts of a rhizomatic process, films complete each other, look at each another: Marie-Pierre Duhamel spoke of films as “holding hands”. Films reframe the tensions that run through our present, bringing out its rugged complexity, its friction, as well as what is in plain sight: the obvious persistence of colonial power experienced by the inhabitants of overseas territories, as shown by the films of Martine Delumeau and Malaury Eloi Paisley in Guadeloupe, by the films of Cécile Laveissière and Jean-Marie Pernelle in Réunion, and by the films of Florence Lazar in Martinique; and the obvious persistence of colonial power which gradually emerges from Mati Diop’s Dahomey, this year’s opening film. Colonialism is again at issue in Soundtrack of a Coup d’Etat, which draws a connection between the American Civil Rights Movement and independence struggles in African countries. It looms large in Raphael Pillosio’s Les Mots qu’elles eurent un jour, which centres on the story of women combatants during the Algerian War, beautifully portrayed by Yann le Masson upon their release from prison. The portrait of these modern and deeply committed women who fought for freedom in 1962 is a reminder that the fight against the patriarchy is neither new nor over. Feminism, if we so choose to call it, will also be at issue in the retrospective dedicated to Claudia von Alemann, and in the films of Claudine Bories, Natacha Thiéry, Sabine Groenewegen, and Kumjana Novakova, among others. Each of these screenings will offer a chance to reflect on the political experience of women filmmakers, on their work, and on their trajectories. And then there is Gaza: not as the event suddenly bursting into our lives and leaving us stunned, as if by some suspension of time, but as something happening to us all and reshaping the way we consider the present, human relations, and our relation to the world. What is happening in Gaza, at this very moment, informs the way we watch films: not only those coming to us from Palestine, but those from Sarajevo and from the Nagorno-Karabakh as well. Catherine Bizern

-

-

-

-

-

-

Claudia von Alemann

In November of last year, a special programme of films presented at the Berlin Arsenal under the title “feminist elsewheres” celebrated the 50th anniversary of the First International Women’s Film Seminar. The event was first launched by Helke Sanders and Claudia von Alemann, who remains a critical figure of German feminist cinema to this day. The 1960s were coming to their tumultuous end and Claudia von Alemann had just wrapped up her studies at the Ulm Film Institute (where she had got to know Alexander Kluge) when she decided to shoot Knokke-le-Zoute’s rowdy experimental film festival, joined the student movement in Paris, and met up with the founders of the Black Panthers in Algiers. Driven by a desire— shared by others—to make counter-information films, she was also eager to do away with conventional forms. Throughout her career, Claudia von Alemann has taken up and brought together a wide variety of filmic languages: from experimental forms to political documentaries, from films in the first-person to historical fiction.

The history of 19th-century feminism looms large in her work, which includes one book and two films devoted to the topic. However, like Flora Tristan—who believed that the emancipation of the working class relied on the emancipation of women—her films address patriarchy and capitalism in the present tense, tackling both topics head-on in the 1972 film The Point Is to Change It, as well as in Nuits claires and in the films she shot in Thuringia after the fall of the wall.

After Nuits claires, the films shot in her home region drew on her family’s story as well as her own, all the while throwing light on the blind spots of German history. From that moment on, her films took a more distinctively biographical turn. They suggest that you cannot speak about others without speaking about yourself, and that you cannot talk about history without delving into your own past.In Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image, the catalogue of “No master territories”¹, a 1976 piece by Claudia von Alemann examines the word “collective”, framing it as a powerful force for thought, resistance, and action. The collective is one of the arguments driving von Alemann’s desire to film and her commitment as a feminist filmmaker. If the intimate is political, then shared experience and the politics of friendship, or sisterhood as we might call it today—as portrayed in The Next Century Will Be Ours and in Nuits claires—are integral to creation. Her latest film, devoted to her friend the photographer Abisag Tüllman, is a graceful expression of this.

Catherine Bizern

_____

¹The exhibition, curated by Hila Peleg and Erika Balsom, was on show at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, in Berlin, and at the Warsaw Museum of Modern Art in 2023.

-

...es kommt drauf an, sie zu verändern

Claudia von Alemann

-

Aus eigener Kraft - Frauen in Vietnam

Claudia von Alemann

-

Blind Spot

Claudia von Alemann

-

Das ist nur der Anfang, der Kampf geht weiter

Claudia von Alemann

-

Denny, Ameise und die Anderen

Claudia von Alemann

-

DISCUSSION WITH CLAUDIA VON ALEMANN

-

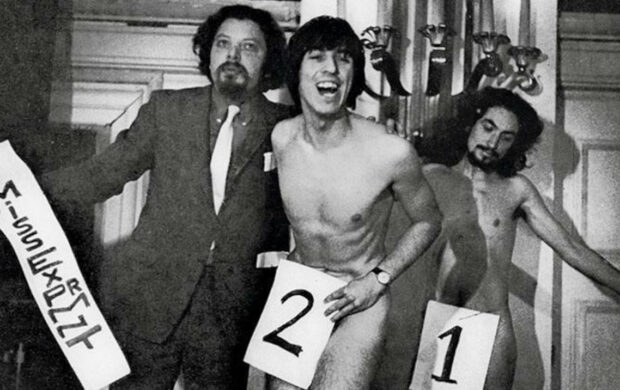

Exprmtl 4 knokke

Claudia von Alemann

-

Die Frau mit der Kamera

Claudia von Alemann

-

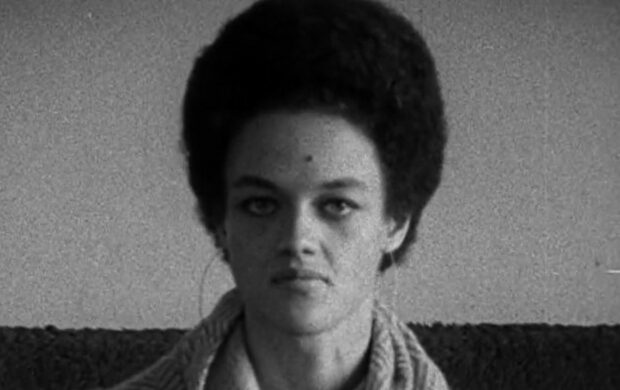

Kathleen und Eldridge Cleaver in Algier

Claudia von Alemann

-

Lichte Nächte

Claudia von Alemann

-

Das nächste Jahrhundert wird uns gehören

Claudia von Alemann

-

November

Claudia von Alemann

-

The intimate and the political

-

THE POLITICAL EXPERIENCE OF WOMEN FILMMAKERS, SINGULAR PATHS

-

War einst ein wilder Wassermann

Claudia von Alemann

-

Wie nächtliche Schatten - Rückfahrt nach Thuringen

Claudia von Alemann

-

-

-

-

-