Édition 2024

“Taking stock of documentary filmmaking as a cinema of mise-en-scene”: this was the idea that gave shape to this edition of Cinéma du Réel, along with the decision to showcase the work of three filmmakers from different corners of the cinematic map. First, with the first French retrospective dedicated to Claudia von Alemann, a pivotal figure of German feminist cinema and one unafraid to mix different languages and narrative devices. Ultimately, these varied approaches coalesce into a body of work that sits at the crossroads of political, shared and personal experience. Second, with the pioneering figure of independent US cinema, James Benning, an avid explorer of America and a keen observer of its history, whose explorations of the country’s storied and eventful landscape create an experience of time and space. Third, with Jean-Charles Hue, whose films, standing halfway between documentary and fiction, plunge us into the heart of a troubled, dangerous and intense reality, in company of the Yenish community in France and with the social outcasts of Tijuana. Documentary filmmaking spans a vast territory whose porous and changing borders allow for formal as well as narrative experimentation. The competition explores these manifold experimentations through a line-up of French and international productions, short- and feature-length, made by emergent filmmakers and acclaimed directors. Experimentation is also the through-line of First Window, a category dedicated to outstanding debut films put forward by a new generation of filmmakers. Popular Front(s) and Special Screenings complete this line-up of contemporary documentary films which investigate and provide new readings of the world we live in. Cinéma du réel also invites viewers to set out on an alternate, more anarchic, and less definite path. Like parts of a rhizomatic process, films complete each other, look at each another: Marie-Pierre Duhamel spoke of films as “holding hands”. Films reframe the tensions that run through our present, bringing out its rugged complexity, its friction, as well as what is in plain sight: the obvious persistence of colonial power experienced by the inhabitants of overseas territories, as shown by the films of Martine Delumeau and Malaury Eloi Paisley in Guadeloupe, by the films of Cécile Laveissière and Jean-Marie Pernelle in Réunion, and by the films of Florence Lazar in Martinique; and the obvious persistence of colonial power which gradually emerges from Mati Diop’s Dahomey, this year’s opening film. Colonialism is again at issue in Soundtrack of a Coup d’Etat, which draws a connection between the American Civil Rights Movement and independence struggles in African countries. It looms large in Raphael Pillosio’s Les Mots qu’elles eurent un jour, which centres on the story of women combatants during the Algerian War, beautifully portrayed by Yann le Masson upon their release from prison. The portrait of these modern and deeply committed women who fought for freedom in 1962 is a reminder that the fight against the patriarchy is neither new nor over. Feminism, if we so choose to call it, will also be at issue in the retrospective dedicated to Claudia von Alemann, and in the films of Claudine Bories, Natacha Thiéry, Sabine Groenewegen, and Kumjana Novakova, among others. Each of these screenings will offer a chance to reflect on the political experience of women filmmakers, on their work, and on their trajectories. And then there is Gaza: not as the event suddenly bursting into our lives and leaving us stunned, as if by some suspension of time, but as something happening to us all and reshaping the way we consider the present, human relations, and our relation to the world. What is happening in Gaza, at this very moment, informs the way we watch films: not only those coming to us from Palestine, but those from Sarajevo and from the Nagorno-Karabakh as well. Catherine Bizern

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

James Benning

James Benning’s preferred way of filming is alone, from life, and out in the open air.

From 1971 to 2007, he worked solo, using a Nagra and a 16 mm Bolex, before turning to digital and HD in 2009. While the length of his takes has tended to increase, the principles of his filmmaking — “Looking and Listening”, according to the title of his class at the California Institute of the Arts—have remained unchanged. A tireless explorer of the United States, he is as much a student in the art of contemplation as he is in the art of the motif. Random buildings, suburban wastelands, country roads, bustling factories, flags flapping in the wind, or characters engaged in mundane activities: by taking a fragmentary approach to the American territory and its vernacular heritage, Benning allows us to embrace it in its entirety.First invited to Cinéma du Réel in 2018, when his film L. Cohen earned him the Grand Prix, Benning has returned to the festival twice, presenting THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA in 2022 and Allensworth in 2023. This year, the festival wished to throw light on the entirety of his work. In the same way that the 2021 film THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA revisited the title of one of his most iconic films from the 1970s, we asked Benning to revisit his career according to one rule: each older film would have to be matched with a recent one, each film shot on celluloid with a film shot in digital. The aim of this was to allow the filmmaker to share his own experience of his work, while leaving it up to viewers to identify both changes brought on by the shift—evolutions in the rigor and in the simplicity of the set-ups—and clues tying each film back to Benning’s larger body of work.

Asking James Benning to curate this programme according to a (minor) constraint was not accidental. Like the literary games of the Oulipo collective, each of his films is informed by a specific rule: 52 still shots, one for each American state, in the 2022 film THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA; a series of shots filmed through the windscreen of a car travelling from New York to Los Angeles in the 1975 version. Whereas the rule, which changes each time, sets a framework, the crucial experience proposed by the filmmaker remains unaltered: an experience of time and space, requiring both patience and an ability to let oneself be overcome by images and sound, or to give in to sensation. It is an experience of landscape as action. Over time, subtle and minimal variations in events, captured by Benning’s camera, reveal the geological and political story of America contained in the landscape: its history of violence and its popular culture.

Catherine Bizern

-

11 x 14

James Benning

-

13 Lakes

James Benning

-

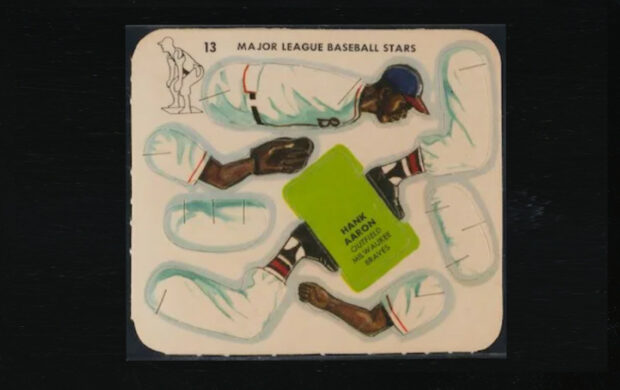

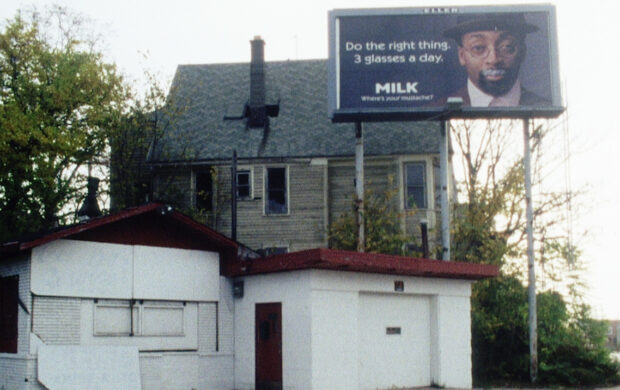

American Dreams (lost and found)

James Benning

-

BREATHLESS

James Benning

-

Discussion with James Benning

-

Four Corners

James Benning

-

John Krieg exiting the Falk Corporation in 1971

James Benning

-

Landscape Suicide

James Benning

-

O Panama

James Benning

Burt Barr

-

READERS

James Benning

-

Ruhr

James Benning

-

SAM

James Benning

-

Stemple Pass

James Benning

-

two moons

James Benning

-

The United States of America (1975)

James Benning

-

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (2021)

James Benning

-

-

-

-