Édition 2025

-

-

-

-

-

-

Four Filmmakers Spurred into reaction / Ryusuke Hamaguchi: Survive, they say

Shot between 2011-2012, the four films (The Sound of the Waves, Voices from the Waves: Shinchimachi, Voices from the Waves: Kesennuma, Storytellers) are driven by the power of the testimonies the filmmakers gathered while travelling along the Sanriku Coast between Miyako (Iwate prefecture) in the North and Shinchi (Fukushima prefecture) in the South. All four films are composed of a series of interviews between two people: duos of sisters, spouses, friends, colleagues, neighbours, or one of the two filmmakers and a person affected by the disaster. Each person’s account of their experience of March 11 is integrated into a more general discussion about life after the disaster, about what really matters to each subject. Each of these interviews has its moments of great darkness but each builds towards a form of comfort that begins with mutual respect. And the striking form of listening in these four films, made possible by the cinematographic device developed by Sakai and Hamaguchi, has remained one of the hallmarks of the latter’s cinema.

To enable the interviewees to listen to each other and free up the viewer’s attention for these exchanges, Hamaguchi and Sakai developed a form of mise en scène (almost a scenography) for the interviews that the filmmakers then repeated identically, filming three, sometimes four hours of interviews and retaining between 15 – 30 minutes of them. The exchanges are introduced by a few cutaway shots of the filmmakers criss-crossing the region in their car, superimposed with an image of a map. These shots make it possible to situate the intimate space – a space for listening and speaking (kiki-gatari), as the filmmakers put it – created by each interview within the geography of the disaster. The interview then unfolds in two stages. At the beginning, each interviewee introduces themselves. ‘We wanted to highlight the artificiality of the situation,’ explains Hamaguchi. After all, as soon as the camera starts rolling, everyone is playing a role: ‘When an individual faces the camera to tell a story, that individual has already started acting’ (Hamaguchi again). During the first part of the interview, the interviewees face each other and are filmed at 270 degrees, with the shoulder of the interviewee in the foreground. This allows conversations to emerge.

Later on, the speakers are filmed in close-up. A drawing representing the person they are talking to has been affixed to the camera. In this second configuration, the impression the viewer has of a face-to-face discussion is, in fact, artificial. The two people are actually sitting next to each other. The gaze of the camera induces more intimate and weighty words, while producing the fiction of a face-to-face encounter. The shot-reverse shot offers a brief let-up in the sometimes-intense expression of pain. It allows us to welcome and hold this pain. In the masterclass he gave at the ENS in Lyon in 2018, Hamaguchi explained that these films had taught him ‘the power of listening’: ‘When one person takes interest in another, listening generates an incredible energy that allows us to see and hear things we didn’t expect’. He also explained that to capture ‘what people hide within themselves’, as Cassavetes, Bresson or Ozu do, and to make a work of ‘cinematographic realisation’ (enshutsu), you have to expose yourself – to ‘offer something to the interviewee, something equivalent to what they are offering.’

The final instalment in the trilogy, Storytellers, reveals the underlying theme of the first three films: the spoken word and a space for authentic communication – the reciprocal ‘space for listening’. Here, this means that stories are stripped of tragedy, as we delve into the oral traditions of tales and legends from Tohoku, following Mrs Ono’s list of stories. It’s easy to see why the interviews in the first three films deal with language as a means of survival in the aftermath of the disaster, and why each interview conveys a unique vision of language as a form of human life. Such is the case with the moving exchange with the young librarian from Shinchi (in Voices from the Waves: Shinchimachi), who confides her discomfort with words, and how much other survivors struggle to speak.

Following an aftershock from the earthquake that almost interrupts the interview, once the sun has returned to the library where the filmed conversation is taking place – and thanks to the encouraging words of her interviewer – the young woman finally conveys her ‘joy of talking’ to the filmmaker and overcomes her inexpressiveness. Then there’s the resident of Minamisanriku who recounts the 11 March, the day she was supposed to meet up with her friend, who was swept away by the tsunami. She talks about the importance of friendship to her, the books they both read, and about the opportunity to talk, to be listened to and understood. These little miracles of documentary speech in each of the four films in the ‘Tohoku trilogy’ are made possible by the device put in place by the directors, which, through its artificiality, liberates voices.

These miracles are also the result of the kindness and gentleness of the two directors/interviewers. Their commitment to the victims is one of the elements that links this trilogy to the Japanese tradition of protest documentary, in which the filmmaker works alongside the victims and inside the image in order to make their voices heard, and against their own self-censorship and the authorities’ efforts at denial. Tsuchimoto Noriaki, for example, filmed a series of films with the victims of Minamata between 1971 and 1975 to inform and educate people living in the area around the Chisso pollution plant about a disease, and to help sufferers gain recognition of their victim status. Documentary filmmaking brings about a process of recognition on the part of the victims, which is achieved primarily through the spoken word. The filmmaker takes on the role of sound recordist in order to conduct the interviews with the victims themselves. What these exchanges have in common is that they reveal to the filmmaker the links that people have forged with their environment: relationships based on work, culture, care and the sea, for example, in the case of the fishermen of Minamata and Aomori.

These four films also form a network of connections with Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s narrative work, which has won awards at the major Western festivals: the Berlinale (Silver Bear for Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy in 2015), Cannes (Screenplay Prize for Drive My Car in 2021), Venice (Golden Lion for Evil Does Not Exist in 2023). The ghosts that crop up in the conversations and tales of the Tohoku trilogy are a continuation of the exploration of loss that lies at the heart of his fictions, in the form of the doubling of and the persistent presence of a missing person in the heroine’s mind in Asako I & II (2018), and The Depths (2010). While the filmmakers explain that they wanted to “make the voices of the dead heard” in their Tohoku trilogy, the dramas, on the other hand, convey the feeling of loss with the kind of disturbing strangeness that mobilises the fantastical. In Heaven Is Still Far Away (2016), a young otaku is possessed by a dead girl who appears and speaks to him. The girl’s older sister makes a documentary interviewing people who knew her younger sister. In a beautiful scene, the young boy converses with the dead girl in front of the camera, gradually leading the two sisters to an exchange beyond the grave. Here Hamaguchi makes a documentary breach into fiction to show how cinema can make the living and the dead communicate, and in so doing extends the documentary endeavour of the Tohoku trilogy.

It’s as if this trilogy of films, seminal and matricial within Hamaguchi’s body of work, has been brewing for a long decade, for the amount of time it took for him to think through the environmental concerns that burst forth in a fine, complex and powerful way in his recent ‘ecological trilogy’, which responds, years later, to the Tohoku trilogy. Walden (2022) and the diptych Evil Does Not Exist/Gift (2023) interrogate the legacy of transcendentalist ecocriticism (Emerson and Thoreau), using the cinematic medium to transform our perceptions of what links us to others, to the living and to our world. With Walden, Hamaguchi surprised fans of his urban dramas by opting for an experimental form (a two-minute still shot of the surface of a pond reflecting pine trees, with Jane Wyman’s voice from Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows quoting Thoreau), and then by using his cinema in service of the music of Eiko Ishibashi and her dissonant strings in the wide-ranging drama Evil Doesn’t Exist, and Gift. Indeed, Hamaguchi continues to dig deeper into this vein of his cinema, which has its origins in his ‘Tohoku trilogy’, inviting us to reclaim our ability to listen and observe, to better connect with the living and the dead.

Élise Domenach

Elise Domenach is a professor of film studies and image and sound aesthetics at the ENS Louis-Lumière, and a film critic for Esprit and Positif. A film philosopher specialising in Asian eco-cinema, she is the author of two books on the cinema of Fukushima: Fukushima in Film. Voices from the Japanese Cinema (UTCP Booklet, Tokyo, 2015) and Le Paradigme Fukushima au cinéma. Ce que voir veut dire (2011-2013), Mimesis, Sesto San Giovanni, 2021).

-

The Catch

Shinji Somai

-

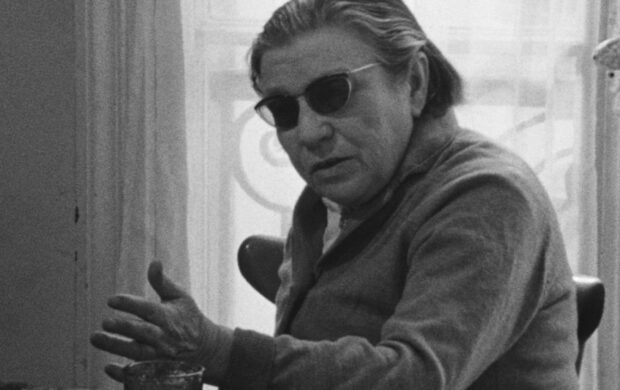

Discussion Ryusuke Hamaguchi

-

Numéro Zéro

Jean Eustache

-

Storytellers

Ryusuke Hamaguchi

Ko Sakai

-

Voices From the Waves: Kesennuma

Ryusuke Hamaguchi

Ko Sakai

-

Voices From the Waves: Shinchimachi

Ryusuke Hamaguchi

Ko Sakai

-

-

-

Four Filmmakers Spurred into reaction / Wang Bing: "Made in China"

The film was presented in three parts last year, first in competition at Cannes (Spring), then at Locarno (Hard Times) and Venice (Homecoming) and it’s easy, when you watch the film in its entirety, to see why he chose to stick with this subject. For almost ten hours – four fewer than Crude Oil (2008), but one hundred minutes longer than Dead Souls (2018) and forty minutes longer than West of the Rails (2003) – the film produces a staggering number of locations and characters. We enter a workshop, whose address appears on screen, followed by the names, ages and birthplace of a few workers who become the protagonists of a plot that builds and develops to its provisional conclusion, before new locations and narratives are introduced. The filmmaker has described this structure, composed of a series of 20-minute segments, as “modular”, concerned as much with the integrity of each story as with their equal weight within the film’s sprawling tapestry. On the surface, life flows naturally. It would be easy to become hypnotised by these young people’s back-breaking labour, and to lend only a distracted ear to what is at stake for them. Sustained attention reveals the richness of a particularly compact narrative, in which the condition of all individuals is expressed through the hardships they face. In the words of Farocki, direct cinema is also a narrative genre.

Of all the episodes, Spring coincides best with the desire, expressed by the filmmaker at the outset of the project, to observe youth in urban centres. We meet teenagers and young adults who play, fight, flirt, unite with and repel one other; thoughtful boys and others like Xiao Wei whose mother ends up taking the rap for his bad behaviour; girls who try to chase off their suitors, and others who use the pretext of trading iPhones to go on dates. Each of them faces dilemmas that convey the insoluble contradictions of the system. At the very beginning of Spring, for example, the question of Shengnan’s pregnancy hangs on the decision of those around her. While her boss urges her parents to let her finish off her quota of clothing, her parents worry about which side of the family the father of the baby will choose. Getting married means that one of the two parties will lose their residency permit, and losing a child also means losing a chunk of household income. Over time, these individual stories accumulate, and group drama comes to the fore. When Chen Qingtao first appears, his composure is instantly noticeable, and everyone seems to see in him the qualities of a negotiator. As the holidays approach, he leads a whole workshop down to the first floor to negotiate their rates per item with the boss; talks that are all the lengthier and more important because, in the absence of a contract, they determine everyone’s return home.

The second part takes up this same architecture, this time highlighting the dispersal of the forces we’ve seen converge. The pace at which the episodes unfold seems to accelerate, and the characters multiply exponentially. There are more quarrelsome, irresponsible or proud boys, whose desire to escape exploitation leads them to stay in bed or go out and play, at the risk of contracting debts or getting into trouble. Xu Wanxiang, for example, emerges from a night in police custody and sets out to recoup what he’s owed from the boss with whom he fought: but the loss of his wage book immediately condemns his demands, the repayment of his debt, and his future in Zhili. Then there’s Fu Yun, a newcomer who messes up a whole consignment of clothes because she hasn’t looked at the pattern carefully. The uncle she calls on to help her out of a jam pushes back when he realises the risk he’s taking; she ends up undoing the seams of the garments, a real Sisyphean task, which she will then redo at a loss.

Like Spring, Hard Times ends up telling the story of an entire workshop, who one day discover their boss beating up a supplier in the street before fleeing. When the fruits of their labour vanish, they are left with the option of paying themselves, unbeknownst to the Labour Office, by selling all the sewing machines to a loan shark. But the loan shark takes advantage of the situation, as does the owner of the premises, who cuts off the electricity that has already been paid for. And then the police try to get them to sign false declarations to make them take the blame. We see how responsibility always falls on the weakest and how, caught between different authorities, these young people continue to live in the cogs of a machine that crushes them, sometimes literally. Nevertheless, many of them return to Zhili, even when, as Si Wen recounts in a terrifying testimony, the slightest protest linked to a tax increase can put them at risk of imprisonment and torture.

In Homecoming, Wang Bing takes the opposite route to the one that led him to Zhili, this time taking a boat up the Yangtze River to follow the return of young workers to their native regions, first to the heights of Yunnan, then to the plains of Anhui province, for the wedding of one couple, and the New Year celebrations of others. By taking to the open sea, the film seems to loosen up a little, extending the nostalgia expressed in a sublime sequence in which two lovers sing to each other across voice notes. There’s a long train ride home, the end of the journey on steep country roads, a traditional wedding in the snow-capped mountains, then a much more prosaic wedding as we return, at the end of the holidays, nearer to urban centres.

Homecoming finally takes us back to Zhili, and to these workers as they choose their workshops and dormitories for the new season. Lin Shao, whom we met at the age of seventeen in a workshop where he worked with his girlfriend, Chen Wenting, is now twenty. His plight as a young father separated from a family that his work must support echoes the story of Shengnan’s abortion at the very beginning of the film. But after the methodical description of the living conditions of this workforce, we can now gauge the extent to which their lives are conditioned by this system, and the weight each of their decisions carries. The overall picture takes the time it needs to emerge: as with the workers, it’s at the end that you get your due.

This is how the narrative of direct cinema works: rather than imposing fictional elements onto reality, it stitches together a posteriori the pieces of a story that present themselves initially in a dispersed and fragmented way. The relative effort required to watch such a film is paid off a hundredfold, as rare as it is to witness such an eruption of narratives. The metaphor of spinning a story takes on a whole new dimension, and we are reminded of the terrifying oracle in Throne of Blood who sings while spinning a yarn: “the lives of men are as insignificant as those of insects”. And if we remember that at the heart of the retina are cone-shaped photoreceptors, essential for colour perception, we come to think that, with the cones of sewing machines constantly being unwound, the filmmaker has discovered in the workshops of Zhili a kind of film studio.

After documenting the end of the 20th-century factory at length, and recording the words of their survivors, Wang Bing has found in Zhili a place of immense vitality within which to continue documenting China’s future, while renewing his cinema from within. Of course, this vitality is neither simple nor unconditional. The industry this energy sustains rests on the cruelly ironic premise that young workers emerge from childhood to make clothes for children, but that they will only be able to have children at the cost of sacrificing their own existence. What kind of life is possible in a system that barely allows for one? We can see how economic forces exert control over life more insidiously but more effectively than the will of the State. Freedom, says Youth in an intractable statement, comes at this price.Antoine Thirion

Antoine Thirion is a critic and programmer, and a member of the Cinéma du réel selection committee.

-

Discussion Wang Bing

-

Youth (Hard Times)

Wang Bing

-

Youth (Homecoming)

Wang Bing

-

Youth (Spring)

Wang Bing

-

-

-

Four Filmmakers Spurred into reaction / Julia Loktev: Counterinformation

Anya, a presenter for the independent TV channel Rain, is the first woman we meet. Often filmed at the wheel of her car, her face soon becomes the projective canvas for both the story and the changing lights of Moscow, from the pale white of early morning, to the golden hues of streetlamps at night, to the crimson of fireworks in Red Square that celebrate the start of the invasion of Ukraine. “Your face is so beautiful right now,” Anya says to the filmmaker abruptly, as the car is stuck at a red light. The faces of all of these women are reflected in each other – up to and including the off-screen face of Julia Loktev. We can’t help but think that the director is the foreign agent, the one who has led a parallel existence to that of her friends, but is now the only one able to document the collapse of Russian civil society and journalism.

Another more discreet tragedy lurks in the images of My Undesirable Friends, emanating from the screens that feature so prominently in Loktev’s shots and her friends’ activities. In the palms of their hands, the film’s activists and journalists hold what might appear to be a small piece of liberal democracy, or at least a means of expression independent of the regime. They all use iPhones, constantly filming and keeping each other informed as events unfold. The progressive Rain channel, where Anya works, broadcasts mainly on YouTube which, she explains, is where part of the outlet’s income comes from. Emails are exchanged over Gmail, and Snapchat and Instagram are referenced… So many applications and communication channels whose facade of progressivism suddenly slipped this January, in service of total adherence to the reactionary policies of the first couple (Trump and Musk).

Mark Zuckerberg, head of the Meta group – which includes Facebook and Instagram – said he wanted to reintroduce a certain “masculine energy” that had come to be lacking within the company, as inclusion policies were put into practice. In the offices of Google – which is owned by YouTube – rainbow flags have vanished along with DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) programs. This represents a general tendency (see also: Disney and Amazon) that the broadcast of Donald Trump’s inauguration showed up for what it was: an American-style oligarchy that stands shoulder-to-shoulder with a far-right president. We have seen tech lords embrace Trumpism, and Trump insult Volodymyr Zelensky with Putin’s words before concluding: “This is going to be great television”.

There’s something doubly tragic, therefore, in watching today’s activists of sound and vision place so much hope in the production of images destined to travel the information highways, just a few years before their direction changed with the wind.

What is striking about these women, however, is their inextinguishable capacity for indignation. Every scandal, every injustice – the closure of the international human rights organisation Memorial, Russia’s exit from the Council of Europe, the daily censorship, the imprisonment of a comrade – is the subject of serious conversation, peppered with some much-needed jokes. Loktev’s undesirable friends force laughs, lots of them, cry very little, and work constantly to keep the truth alive.

A moral compass – one they have improbably borrowed from Harry Potter – regularly guides their steps (although references to The Lord of the Rings also occur when, for example, Lena tells her partner who has come to join her in Moscow from America: “Welcome to Mordor!”). As the situation grows increasingly desperate, and when it becomes apparent that exile is their only recourse, references to the famous saga became more and more frequent. The invasion of Ukraine is compared to the fall of the Ministry of Magic (Deathly Hallows), Navalny is likened to Harry (whom he is said to have quoted at his trials) and, logically enough, Putin is none other than Voldemort, with whom – as Ksyusha remarks shortly before the police enter Rain’s studios – he shares a certain physical resemblance.

A few belongings thrown into a suitcase, a plane ticket to Istanbul bought in a rush: the film is suddenly depopulated by its characters, who leave their country one after the other. The first images of the invasion of Ukraine are still fresh in our minds, but those of Russia’s tipping over into martial law are still rare. Julia Loktev is there, in the midst of the tumult that the edit of My Undesirable Friends aims to render at the end of the film, by imitating the editing of the programs broadcast by Rain in its final moments. Which images, which narratives, remain when the faces the series has accustomed us to seeing and hearing have left the frame for a distant off-screen? A title card at the end promises a second part to the series, soberly entitled Exile.

Occitane Lacurie

Occitane Lacurie is a critic for Débordements magazine and a doctoral student in Film Studies.

-

Discussion Julia Loktev

-

My Undesirable Friends: Part I - Last Air in Moscow

Julia Loktev

-

-

-

In Ghassan Salhab's workshop

-

Night Is Day

Ghassan Salhab

-

Workshop 1

-

Workshop 2

-

Workshop 3

-

Workshop 4

-

Workshop 5

-

-